Rethinking retirement: Youth, uncertainty, and the philosophy of work

Sep 02, 2024

9 mins

Journalist

Once seen as a natural step in any successful career, retirement is now viewed as little more than a pipe dream by many Americans. When asked when they planned to retire, one in five said it might never happen for them, mostly for financial reasons. Confidence is lowest among those aged between 22 and 34, according to a recent TIAA Institute survey, 21% of whom said retirement is “out of reach” or not part of their plan. This latent uncertainty about the future can be expected to have an effect on how young people feel about their daily work and their careers.

To understand the driving force behind this uncertainty and what this means for the future of young workers, we spoke with Professor Paul Blaschko, an assistant teaching professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. Blaschko teaches courses on life’s big questions and the philosophy of work. He co-wroteThe Good Life Method, which looks at how philosophy can be used to help us live better lives, and directs a program in Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters devoted to “exploring how the humanities can help us find meaning in work.”

A lot of young people think they won’t ever be able to retire, what do you think of that?

There’s a perception amongst my students—and some young people I’ve read about—that the economy is changing so quickly, and so many technologies have developed over the past 20-30 years that the workplace is going to be radically different in another 20-30 years.

There is an idea that things will change so rapidly that it’s hard to predict what life will look like mid-career or late-career. There may be more changes in careers and less stability over the long term. So, there is a lot more uncertainty about it. I think that the assumption that one will be able to retire and know what that looks like has been undermined for this generation.

What kind of impact can the idea that they can never stop working have?

Retirement used to be seen as a goal. You work for the purpose of retiring and then your life becomes your own. You can play with your grandkids, travel, and do whatever else you always wanted to do. I’m not sure that has ever been a common experience of retirement. Philosophically, retirement is the endpoint, the thing you’re working towards. And if you’ve got a goal like that, then it’s easy for you to instrumentalize, or use your work as a means toward that end.

Young people are not thinking about work in that way now. Maybe that’s because of the uncertainty of whether they’ll be able to retire or what retirement would look like. That changes what they’re looking for from their working life.

If my work isn’t just this thing that’s going to allow me to make enough money to do what I want in the future, then that changes how I look at the work. It makes my career, my job, my work, more intrinsically valuable. Or, it might lead me to look for more intrinsic value from the work.

So, their main concern is not making a ton of money. For many of them, their main concerns are, “Will this leave me satisfied? Will I find this work meaningful? Does it have a purpose that I really endorse? Is it capable of making an impact in the world and changing lives?” They’re concerned with existential values.

We see employers responding to this too. A lot of jobs are being sold as an “experience,” you’re part of a greater movement, of something greater than yourself. You might think that considering work in this way is going to draw you more into the working world and more into your work. And for some people, it has that effect.

On the other side, for some, you see a desire to subordinate their work to other more near-term goals, to their other passions, and to other things that they find intrinsically valuable. I see this most often with former students who have worked for five or 10 years. It could mean remote work or hybrid work or gig work. It could mean traveling around picking up work where they can, supporting their immediate needs. Life is going to be lived in other areas. It’s not going to be lived in the workplace.

Do you think there’s resentment against older people who can retire younger?

There’s certainly a sense that the generations don’t understand each other or each other’s motivations very well. And maybe resentment captures some of these attitudes. When I talk to groups of older people, they’ll ask a lot of questions like, “Why do these younger people coming into the workforce expect so much? They seem entitled. They seem to assume that they deserve a certain amount of time off, to work remotely,” or whatever it might be.

On the flip side, younger people might look at somebody who’s a senior partner in a firm and say, “Of course you’re going to work 80 hours a week. You’re making millions of dollars and you can do whatever you want.” Those differences of expectations lead to mutual unintelligibility or at least mutual confusion in the workplace.

Can philosophy help people to get on in the modern world?

Certainly. If you go back to the foundations of philosophy—Socrates, Aristotle, the Stoics—they saw philosophy as a way for us to think about what’s most valuable in our lives, and then to reflectively organize our lives so we can realize those values. So, for them, philosophy was a way of life rather than the abstract study of theory.

We can learn a lot from the practice of philosophy. Let’s take the example of Stoicism, which has become really popular in recent years. Stoicism is a way of breaking out of certain presuppositions that people feel they’ve internalized from the culture. The basic Stoic view is that if you’re attached to external things—wealth, status, power—then your life is going to be precarious in a certain way. Because there’s no guarantee that you’re going to become wealthy or have the power that you want.

So the more you invest in those things and value those things, the less inner peace, harmony, or tranquility you’ll experience—and the more anxiety. The Stoics had concrete suggestions about what to do, which look a lot like practices that we find in cognitive behavioral therapy. The Stoics said: divide things up into what you can control and what you can’t control, make sure that what you value is something you can control, and if you value something you can’t control, you can try to detach from it.

Reflect on your own death. Just think for a second, “In 50 years, I’m going to be dead. No one is going to care whether I wrote this email today or tomorrow.” That gives you distance from the thing that’s causing you anxiety.

So, if you work for any amount of time, you’ll find yourself valuing professional status though you’ve never reflectively thought about it. There’s nothing wrong with status. Status, esteem, and respect are part of our operating system and psychology as human beings.

But it’s really easy to get carried away by these things. In Alain de Botton’s book Status Anxiety, he looks at these concerns from a broad historical and cultural perspective. Understanding and grappling with this drive for status, this really powerful force, can be a way of getting distance—reflectively—from those desires. The Stoics were masters at this.

Can this help us in thinking about a long-term future without retirement?

Getting a broader perspective can help, and philosophy is the place to go for that. Aristotle has a way of helping us articulate what it is we care about and value in life. For Aristotle, everything we do aims at some goal. His concept of eudaimonia, [meaning] happiness or flourishing, includes making sure you’re aiming at the right goal. Understanding what that entails can help you gain reflective distance or agency over those things that otherwise would drive you through life less reflectively.

My happiness consists in a really essential way in the flourishing of my family—I’ve got four little kids. This is an important piece of what it means for me to be happy.

By identifying this as part of my primary purpose in life, I can think more clearly about what I want the shape of my life to look like. I want to have a job and make money now, but not at the expense of spending time with my kids. On the other hand, I need to invest enough in my work now so that I can have the means to maintain these relationships as I get older. Using Aristotle’s framework, then, can help us make sure that our working life is really serving the things we value most, both now and in the longer term.

Are there more important driving factors than long-term goals, such as retirement?

If you’ve got a longer-term goal like retirement, and you see clearly what the steps are to achieving it, then that gives you shorter-term goals that can make a more gradual career trajectory intelligible and feel like it’s a good practical decision.

But not having a set of long-term goals makes each next step all the more urgent. It has made the achievement of near-term markers important for young people. They think, “If I don’t succeed at this right away, maybe that means I’ve stagnated and I’m going to stay in the same spot forever.”

Does anything in your next book touch on this topic?

Yes, I’m looking at transitions in our working life, such as retirement, that involve moving from a highly structured working environment to one where we’ve got a lot more autonomy and control over what we’re doing. One thing that’s important to think about is where the sources of ultimate value are in life.

Aristotle distinguishes between ultimate value and instrumental value. The things that you’re doing because it gets you something else—instrumental value—versus the things that are meaningful and intrinsically valuable, good for their own sake.

People who are going through a transformative experience in their working lives are often willing to defer things that they think are of ultimate value in order to get to a goal—such as retirement—because they think it will better set them up for the ultimate value.

But there are traps that encourage us to defer pursuing something of value in the moment that could really set us up in the future. You might think, “Once I’ve made my first $1 million, then I’ll spend time with the kids, and then I’ll be happy.” That’s a classic case of a big picture error because you fail to realize that part of the essential, ultimate value of having a family is raising those kids and being with them.

It’s important to realize that a lot of the things that we think of as having ultimate value require skills that we’ve got to build up over the course of a lifetime. They’re not the sort of things that we can just start doing the moment we retire. For example, Aristotle tells us that part of what is so good about being human, and part of what makes us human, is that we’ve got this ability to contemplate, reflect, and appreciate the world on an intellectual level.

If I spend my whole career so deep in the weeds with my job, and I never develop the intellectual capacity to contemplate, appreciate, and connect with reality in a certain kind of way or on a certain intellectual level, I could find myself at the end in retirement without that skill. It’s a skill that you’ve got to cultivate and develop throughout your life.

If you’re lucky enough that you can do it, it’s worth thinking about these ultimate values and the skills they require and about spending time learning those as an investment in yourself for the future, and not letting the financial questions crowd those out. If you can explore those values and think about them throughout your life, that may change your vision of what retirement looks like.

A lot of time, we think of values as a set of things we have. Philosophy provides ways of thinking about the value, meaning, and purpose of life that could challenge us and make us grow. We could end up rejecting some values and finding others.

Philosophy is a great way of putting us in conversations with people who can challenge us to grow so that we’re not arbitrarily operating on the values we happen to have or that we’ve internalized from our culture. But we’re really pushing ourselves to grow.

As a university employee, how do you feel about retirement and the future?

We’ve got four kids under seven, so I’m at the stage where we are starting to think about these long-term questions. We have a financial adviser and we’ve mapped things out, but day-to-day I don’t think about it a lot, partly because there are other hurdles, such as putting kids through college.

There are times when I sit down and talk to my wife, think about it and make plans, but even for me it’s an imaginative exercise. I just assume the world is going to change in crazy and unpredictable ways for the next four to five to 12 years. So I’m like, “You know, things are good. We’re taking care of the family. We’ve got a good plan. We’ll go from there.”

Photos by Barbara Levant for Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every week!

More inspiration: Future of Work

The Bear: When professional passion turns toxic

Carmy's workplace trauma isn't unique...

Dec 31, 2024

The youth have spoken: South Korea’s push for a four-day workweek

Is this the end of Korean hustle culture?

Dec 26, 2024

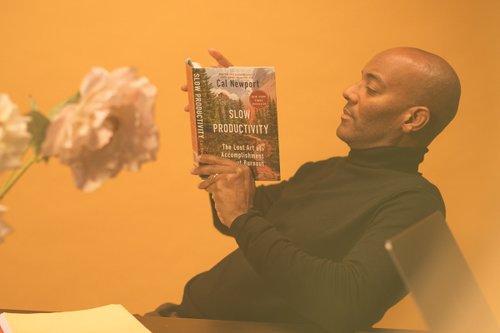

Cal Newport's Slow Productivity: Redefining success in a hustle culture

Is slowing down the key to achieving more?

Dec 19, 2024

Wellbeing washing: Are workplace mental health apps doing more harm than good?

Workers are struggling with mental health. Are employers approaching it the right way?

Dec 19, 2024

Dark side of DINKs: Working as a childfree adult

Having children comes with challenges. So does choosing not to.

Dec 11, 2024

Inside the jungle: The HR newsletter

Studies, events, expert analysis, and solutions—every two weeks in your inbox