James Flint: from tech journalist to tech for good

02 juin 2021

8min

Journalist

James Flint always knew the internet would change the world, even before it became popular. That’s why he spent most of his career writing about it. From founding an underground tech and art zine to becoming editor-in-chief at the Telegraph Weekly, his fascination for the digital revolution never withered.

After more than 15 years as a journalist, Flint’s disillusionment with the media industry eventually pushed him to switch career paths. So in 2014, Flint co-founded Hospify, a messaging platform for healthcare workers that guarantees data privacy. This is the story of how a pioneering tech journalist used his expertise to do tech for good.

“What was I saying?” James Flint asks me, having lost his train of thought after telling off his teenage daughter for interrupting our interview. “You were using an analogy of a boat to describe what it’s like to start your own company,” I reply. “Right,” he says, “Running a business is never something I would have imagined for myself during all those years as a tech journalist, but now I see the beauty in it. It’s like building a boat. You’re not thinking about money, you’re thinking about how to make the boat more stable, how to make it sail through the economy better, how to make sure your crew is alright, and how to make sure your family is okay. The narrative you’re presenting to the world is a financial one, but what drives you is the reality of the ship,” he says.

The boat that Flint is talking about is called Hospify. It’s a secure messaging platform designed specifically for healthcare professionals and patients. Flint founded the company with two NHS surgeons, Neville Dastur and Charles Nduka, in 2014. They had found that faced with outdated communication tools such as pagers, emails, and landlines, 600,000 NHS professionals were using WhatsApp to communicate. But the data that is stored when using WhatsApp means the platform is not safe to exchange secure messages on. So Dastur and Nduka wanted to build an alternative and went to Flint for external expertise.

“Running Hospify is about getting the things we love about technology: the convenience, having incredible computers in our pockets, speaking to anybody, going anywhere – without the price of your behavior being monitored,” Flint explains. The app was inspired by peer-to-peer networks from the 1990s and 2000s, such as Napster.

Flint has witnessed the growing role of big data firsthand, first as a tech journalist in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and then as an editor-in-chief when newspapers were going online. The monetization of data is something he wants Hospify to avoid as chief executive. “I want to make the business model work without advertising, without selling the metadata, because I don’t agree with that approach,” Flint says. “I’m prepared to put up with it if I’m buying a washing machine, but not if it has to do with health or mental health or any kind of politics.”

But how does a journalist end up becoming the chief executive of an innovative tech company? How did Flint go from traveling down rabbit holes, uncovering the depths of the digital revolution, only to be spat out in the world of business?

Philosophy, psychology, and the birth of the internet

Flint grew up in Warwickshire, the birthplace of Shakespeare. At age 10, he was in a car accident that left him bedridden for two months. While convalescing, he discovered the magic of books. “It was only logical that I decided I would become a writer,” he says.

He went on to study philosophy and psychology at Oxford University. Flint says, “It was a degree that really ended up defining my life. It was a real split between art and science, which is what my career has been.” After a brief stint in New York studying jazz, he completed an MA in philosophy and literature at the University of Warwick in Coventry. It was around this time, In 1992, that Flint discovered the internet.

Flint was thrilled to see that people were discovering new methods of thought, using non-linear thinking to solve problems. He became intrigued by parallel processing (running two or more processors to handle parts of an overall task in computing) and neural nets (computer systems inspired by biological neural networks), constantly reaching for the bigger picture of what this would all mean for humanity. So Flint decided he would write about it.

“I was more interested in words than money”

Flint moved to London in his early 20s to become a journalist, starting out with an internship at The Independent as a picture researcher and postboy. “I was more interested in words than money,” he says. “So instead of trying to start a web company, I decided to write about the internet and use that as my way into [the industry].” His goal was to popularize things that were buried in pockets of science and technology.

Flint wiggled his way into getting published for the new technology section under a pseudonym. Meanwhile, he founded an art and technology zine called Mute with other writers interested in exploring culture and politics after the internet. Then, in 1996, Flint was headhunted by Wired UK to join them as a journalist.

“It was the best job I ever had,” Flint says, before correcting himself to say that running his own business is even better. “It was amazing. Suddenly, we were plugged into the San Francisco machine. We were kind of an outpost of Silicon Valley,” he explains. In his two years at Wired, Flint wrote about subjects that are still widely covered today: cryptocurrencies, electric cars, digital art, PGP (Pretty Good Privacy). Yet the world around him seemed hesitant to jump aboard the revolution he was reporting. “We were trying to tell stories of why people should take advantage of the opportunities and how these technologies will change the world. No one believed it,” he says. “[Then] in 1998, just as the dot-com boom was going crazy and we were being proven right, Wired went bust and I found myself out of a job.”

Ups and downs

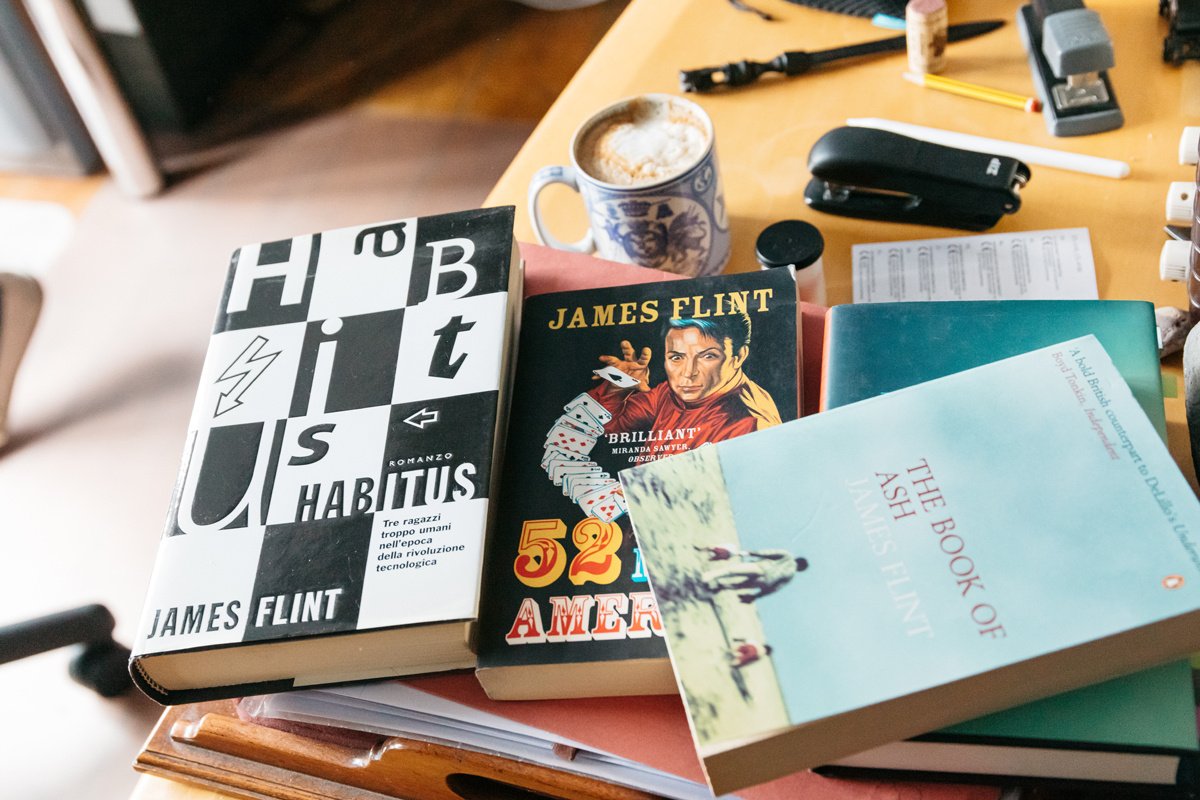

With the little redundancy money he got from Wired, Flint finished his first novel and, just before turning 30, got a great book deal. He felt things were looking up. “I was suddenly a young novelist writing about the future. It was the dream,” he says. “It’s what I had wanted since I was 10 years old.” He started writing his second book and eventually was offered a job at the BBC for the broadcaster’s FictionLab, a new digital channel.

“I was hired to create a social media drama before social media existed. Through a website, you’d have your own apartment in this giant tower block. We would run a drama that you could watch over the CCTV cameras. People had their own personas and would interact with one another… It was a kind of murder mystery,” he explains. As a producer, he helped to design the platform and co-author the drama. But after about 18 months, Flint’s career came to a halt again. “I was in the canteen and on the TV I saw the airplanes flying into the Twin Towers. The whole project was shelved because of the sensitivity of trying to do a drama in a tower block.”

Flint describes this as a “volatile time”. The turn of the millennium came, followed by the dot com crash and 9/11. He tried to get his second book published but it was rejected. He wrote another book to get out of his contract, and his father was diagnosed with leukemia. By now, he was in his mid-30s and running out of money. “I was earning so little that I got investigated twice by the tax authorities,” he says, laughing. “And I just thought to myself: I’ve got to get a job.”

He joined the Telegraph as a features editor in 2006 and by 2009, had worked his way up to editor-in-chief of the Telegraph Weekly World Edition. Newspapers were beginning to take publishing online seriously and part of Flint’s job was to digitize the Telegraph. “I found it fascinating. The world was beginning to turn again. Facebook and Google were on the rise. I was either editing or writing about these companies, about shifts in the business world. My worlds of technology and writing were aligned once again,” he says. “I started to realize that business is really creative. I met a lot of people who were making an incredible impact with their companies.”

‘I stopped seeing the only worthy output being stories’

While his attitude towards business was shifting, so was his passion for journalism. He watched the Telegraph try to compete with Facebook and Google, narrowing their content to sell more and more ads. The reasons he had wanted to become a writer at 10 – the joy of the intellectual idea, the broadness of thought, storytelling, the ability to open conversations – no longer seemed to have a place in the industry.

“As I was seeing the creative possibilities of business, around me, the world I had spent three decades absolutely loving and being obsessed by, I felt, was being eviscerated and narrowed,” he says. “For the first time in my life, I stopped seeing the only worthy output being ideas or stories. I started to see that worthy outputs could also be processes, materials, services.” So when he was told that the Telegraph’s weekly newspaper would have to be shut down, Flint took voluntary redundancy.

Suddenly, CEO?!

About two years later, Flint was contacted by Dastur. Knowing Flint had built up solid technological skills and had experience in managing digital platforms, Dastur was keen to run an idea by him. He explained to Flint that the NHS was still using archaic ways of communicating internally and externally.

When he performed surgery, for example, the contact details of assistants and surgeons were simply tacked onto a wall of the theater. When this went missing one day, he and Nduka decided they needed a more modern solution.

After doing some digging, Dastur, Nduka, and Flint found that hundreds of thousands of healthcare workers in the UK and Europe used WhatsApp to communicate. There was no secure messaging platform available. So they decided to build one and to call it Hospify. Dastur built a tester and Flint got them onto an incubator program which gave them money and support. Then, in 2014, they set up the company.

“It was difficult to sell the product for the first few years. We are only just starting to scale our company,” Flint says. Following the introduction of the European data protection regulations in 2018, interest in Hospify grew. Healthcare institutions could suddenly be liable for up to 4% of their annual turnover if patient-identifiable data was not handled securely. In 2019, they launched a paid version of the app called Hospify Hub where users’ data can be stored (the free app deletes any transit messages after 72 hours, and deletes data from phones after 30 days). After Covid-19 hit in early 2020, Flint said he had “never worked so hard”. The Track and Trace app got people thinking even more about data privacy and, with remote working on the rise, the demand increased for efficient digital tools such as Hospify. “We saw our user base quadruple between March and July 2020,” Flint says.

Today, Hospify is being used across 200 clinical sites in England and is the only general messaging app to be approved by the NHS Apps Library for use by patients and clinicians.

Looking back at his career, Flint says: “I feel lucky to have been one of the writers in that period that was part of a bigger conversation. I’m proud of that,” he smiles. “I was a contributor to what was an incredible global conversation. I’m happy to have participated, and I hope to be participating again today with Hospify.”

Photography by Lucas Bullens for Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

Inspirez-vous davantage sur : Tech for good

How neurotech could boost your performance at work – or endanger your human rights

Neurotech is already being used to monitor workers’ concentration levels and assess their emotional skills...

17 janv. 2024

‘Silicon Valley isn’t the tech world’s only model of inspiration!’

The short life of software on our phones is as bad for the environment as it is for our wallets. Agnès Crepet shares how she uses tech for good!

28 sept. 2021

The only way is up: farmers who grow crops without soil or sun

Vertical farming, hailed as the "future of farming", needs a whole new set of skills never before seen in agriculture. What's behind the hype?

22 déc. 2020

Taking on tyrants: UK tech workers unionise for better rights for all

Everything you need to know about the United Tech and Allied Workers Union (UTAW), UK's latest tech workers' union.

09 déc. 2020

Andy Hunter: from IT to bookshop.org, the underdog taking on Amazon

Bookshop.org's founder tells us about his career in the world of literature, how he was once an 'IT guy' and how he juggles several jobs at once.

24 nov. 2020

La newsletter qui fait le taf

Envie de ne louper aucun de nos articles ? Une fois par semaine, des histoires, des jobs et des conseils dans votre boite mail.

Vous êtes à la recherche d’une nouvelle opportunité ?

Plus de 200 000 candidats ont trouvé un emploi sur Welcome to the Jungle.

Explorer les jobs