What no one's saying about neurodiversity in the workplace

Jun 13, 2023

9 mins

Journalist and translator based in Paris, France.

Inclusive hiring programs have changed lives for some people who are considered neurodivergent. But does that mean that they are enough? Is it a good idea for businesses to try to “leverage” neurodivergence? With the help of experts in this area, Welcome to the Jungle investigates the complex truth about neurodiversity at work.

Leora Sali was anxious about her son. He was autistic, and struggling to find a place in society. This was hard for Sali to witness because his suffering felt needless. She knew he had exceptional powers of concentration, powers that she believed could help him to earn a living, thus boosting his self-esteem. As a physicist for Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, she felt sure that the uncommon abilities found in certain people on the spectrum could benefit the military, and convinced her employer to investigate the idea.

Sali is a co-founder of the Roim Rachok program launched in 2013. This Israel Defense Forces program trains teenage Israelis on the autism spectrum in aerial photography analysis, cybersecurity and information sorting, among other tasks. More than 300 of these soldiers now serve in 27 divisions including elite units, and they have been praised for their ability to complete mentally taxing work in a way other soldiers cannot. The program, which was designed to accommodate the trainees’ needs, has since been copied by other militaries, and graduates have gone on to work for private companies such as Intel.

It’s exactly the kind of story the business world promotes when discussing neurodiversity. The term refers to the idea that people with various cognitive and behavioral traits all have a role to play in society — and the workplace. In the past decade, there’s been an uptick in the number of hiring initiatives aimed at neurodivergent candidates, or those who think, learn or act differently from the majority of their colleagues. These include — but are not limited to — those with autism, ADHD and dyslexia. Like Sali’s son, many people with such conditions have a hard time finding and keeping jobs. The unemployment rate is at least 30-40%, according to one estimate from the University of Connecticut’s Center for Neurodiversity and Employment Innovation, which notes that there are few resources to track specific figures. And like Roim Rachok, the hiring programs implemented by big employers such as Google, IBM and Goldman Sachs have raised significant awareness that these people shouldn’t be left out of the labor market.

As neurodiversity became an HR buzzword, articles were published in the business press and online explaining how companies could “leverage” such employees to gain a “competitive advantage.” While Roim Rachok is composed of hyper-focused tech geniuses whose productivity can be unlocked with the right accommodations, these soldiers represent only a percentage of the autistic population, let alone of the neurodivergent one. Not all neurodivergent workers are savants, Stem-oriented, or want to be superstars. Some require intense accommodations. Many eschew the term “neurodivergent,” which is used in this article for explicative purposes.

Getting past the idea of superpowers

Neurodivergent workers can make excellent employees, but the implication that they all harbor revenue-boosting superpowers is misleading. It glosses over the headaches that can arise when a business tries to integrate a variety of cognitive and behavioral differences into today’s workforce. Here’s why:

The Rain Man fallacy

Many on the autism spectrum complain of being erroneously compared to the protagonist of Rain Man, a 1988 movie that propelled the stereotype of the autistic savant into our popular imagination. “It’s been assumed that I’m very good at computers. I’ve been assigned a lot of tech-based tasks, and I would have to learn how to do them. Even though I was not as great at them as I was expected to be,” says Haley Moss, an autistic lawyer and neurodiversity advocate. The term autism — like neurodiversity — encompasses a kaleidoscope of different brains, from exceptionally articulate people like Moss to those who are non-verbal. Recent research from Weill Cornell Medicine suggests there are at least four subtypes of autism, and they’re not all math whizzes.

Yet the neurodiverse hiring trend was led by highly profitable tech companies such as SAP and Microsoft, which are known for their ability to attract the world’s top talent. And tech skills are highly coveted in the labor market, accounting for seven of the 10 most sought-after hard skills on LinkedIn. Combine these factors with the persistent Rain Man fallacy, and it’s easy to see why employers with little neurodiversity training might think they could cash in on neurodivergent employees, especially autistic ones.

Moss says she fulfilled her employer’s tech-based demands because she wanted to prove herself. “It made me feel very frustrated and stressed because I wanted to do a great job, and I wanted whoever hired me to be proud of me, and not to regret hiring me,” she says.

This misguided notion about tech skills puts the onus on the tech industry to boost neurodiverse employment – even though every sector could benefit from having neurodivergent employees.

“Most of the structured programs, frankly, are around the tech field or having to do with tech jobs. But those of us who are pushing [employment of those on the spectrum] are pushing it in all sectors and all occupations,” says Michael S Bernick, an employment attorney with Duane Morris, a former director of the California Employment Development Department and a longtime advocate for jobseekers with autism. “The great, great, great number of people diagnosed on the autism spectrum have no particular exceptional tech skills. So they’re going to be in jobs in administration, in retail, in health care, in a range of other fields,” he says.

The right to be average

While autism gets much of the attention, those with conditions such as ADHD and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) are equally encouraged to channel their neurodivergence into professional greatness. “If you are a neurodivergent person and say being neurodivergent is your superpower, I will never fight you on that, because that is how you identify yourself. That’s beautiful. I love it, because I have a similar take,” says Moss. “But when other people are telling me it’s a superpower, I feel weird. What if I don’t have that exact same superpower that you’re looking for, or it’s not as consistent as you would like it to be?”

Moss worries that unrealistic pressures from employers create burnout within her community. An estimated 85% of Americans with autism are unemployed; the anxiety around meeting standard work expectations is already high enough. Some workers don’t even feel comfortable disclosing their neurodivergent traits to their bosses. Moss says there are many valid reasons for this, “especially if you’re someone who is multiply marginalized. You might not feel comfortable or safe. There’s a worry that you’re subjecting yourself to even more from an intersectional standpoint.” While certain neurodivergent employees get a confidence-boost in the limelight, others just want to be part of the company, like everyone else.

And neurodivergent or not, climbing the corporate ladder is no longer part of the US zeitgeist for increasing numbers of employees. A significant portion of the workforce is fed up with the hustle culture, taking an anti-work stance and quiet quitting their jobs. Just like other workers, there are neurodivergent individuals out there who don’t want to tie their self-worth to their career, or be “leveraged.”

“I wish there was more [written about autism] that wasn’t just focused on everything that’s hard or this extreme gift,” says Moss. “I wish there were sometimes, just something in the middle. But I feel like that doesn’t always make for a great story.”

Accommodating needs

From Roim Rachok to JP Morgan, every organization with neurodiversity training knows the key to success is adapting to the employee’s needs. For some individuals, this could mean a quiet sensory room where they can focus. For others, it may mean remote work, or a specific type of guidance from their manager. And there are certain employees who require constant oversight, or a full-time aide.

“People with autism, the neurodiverse, are unemployed and underemployed, and it comes across like it’s employers who don’t want to employ them. Oh my gosh, that’s not fair to employers. That’s not true,” says Eric Steward, director of the Transformative Autism Program (TAP) at Meristem, an institution that prepares neurodivergent young adults for the workforce and trains companies in neurodiverse inclusion. “But it also comes across like you have all of these neurodiverse people standing by, ready to join the workforce, and they’re going to be super-reliable and capable. And that’s not true either.”

Plenty of neurodivergent employees need just a few simple workplace adjustments. But not everyone will transform into a lean, mean autonomous machine just by having a sensory room. “There’s a lot of folks that still have a lot of learning to do to just be able to meet the baseline needs of any employer on a consistent basis, whether it’s entry level or mid-level,” Steward explains.

To illustrate these real-world coundrums, he gives a fictional scenario:

- Sally, a neurodivergent candidate, works hard to learn new skills, find an accommodating employer and navigate the hiring process.

- She finally lands a job with XYZ, a company that has put time and effort into fostering a neurodivergent-friendly workplace. Together, they put a plan in place to ensure Sally is comfortable and productive. XYZ re-organizes its schedule so Sally can work at the times that suit her best. A designated employee is assigned to be Sally’s buddy, acting as the consistent, familiar face Sally needs to remain calm and focused.

- A few months into the job, Sally’s buddy is hired elsewhere and leaves the company. This is very stressful for Sally, and disrupts her ability to work properly.

- Alternatively, Sally’s buddy stays, but Sally can’t commute to work herself or find transportation help, and XYZ doesn’t have the budget to pay for a private car.

- In a third scenario, Sally starts dating a romantic partner for the first time in her life. Although Sally and XYZ have both been honoring her work plan, this new life development makes it very hard for Sally to concentrate or complete her tasks.

In these cases, Steward says, “the employer has every right to go, ‘Hey, I tried. I didn’t expect all of this work to go into hiring this one person.’” In his experience, the vast majority of employers genuinely want to make neurodiverse hiring work, but the obstacles can be hard to surmount.

Unfortunately, the argument that neurodivergent people should be hired because they offer a great return on investment overlooks difficult cases like Sally’s. Worse, it implies that Sally doesn’t merit employment. Not only is Sally a great addition to XYZ’s team when the conditions are right, but Sally, like every citizen, deserves a job.

“There should be a place in the job market for those people who are non-verbal or have very severe impacts,” says Bernick. Co-author of The Autism Full Employment Act, Bernick does not believe these jobs will be created by the market alone. Both he and Steward feel the biggest improvements will come with policy, such as ensuring transportation for those who need it, or increased funding for the job coaches of neurodivergent employees. Speaking about neurodivergent workers like assets rather than individuals frames the situation as a private sector issue, discouraging the public sector from making these vital changes.

Everyone is an individual

As the term “neurodivergent” encompasses such a wide range of abilities and backgrounds, accommodating these candidates requires a highly tailored process. “Don’t try to hire 100 autistic people because you think that you’ve figured out some matrix,” warns Steward. “That’s not fair to the individuality of the autistic person.”

Moss adds: “What I always like to tell companies is, ‘Just make everything as accessible as possible and reduce the need for anybody to require accommodations.’ Which is really just taking a universal design approach to work, leveling the playing field to make things as accessible as possible to as many people as possible. Because in an ideal world, nobody really needs an accommodation.”

Many different workers demand accommodations from their employers, from students requiring flexible schedules to caregivers who need to work from home. However, all employees have different needs, challenges and capabilities that affect how they work, whether they have a diagnosis or not.

What’s more, the idea that some people are “neurodivergent” implies that everyone else is “neurotypical,” but there is no standard human brain. No two employees concentrate, stress, socialize or cogitate in exactly the same way. Significant members of the neurodiversity movement reject the idea that people with autism, ADD, and other such diagnoses are separate groups from the rest of society. Judy Singer, the Australian sociologist credited with coining the term “neurodiversity,” wrote recently, “The whole point of the #Neurodiversity Paradigm is that together we make up the whole human tapestry. We all have different roles to play.”

Bernick, who feels similarly about the term “neurodivergent,” adds: “Autism is really an empty phrase these days in the sense that the spectrum of skills, abilities, and limitations is so wide that it’s hard to talk about… Politically, I can see why it’s used, and I use it. But it is a category that needs a lot of refinement. You know, we’re all neurodiverse.”

Steward agrees with that take. “I don’t see anybody as a savant,” he affirms, noting that even “high-functioning” tech engineers with autism suffer meltdowns when their work is overwhelming. Moss points out the most common office accommodations for neurodivergent employees actually benefit all workers, from quiet concentration stations to clearly communicated agendas. “The elements of making an effective neurodiversity program,” says Bernick, “are really ones that benefit all employees.”

Inclusivity efforts have come a long way in the 25 years since Singer coined “neurodiversity.” Weaving the whole human tapestry into our workforce, however, won’t happen by measuring everyone’s business value. Instead, we must meet all workers — and reality — where they’re at.

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook on LinkedIn and on Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: DEI

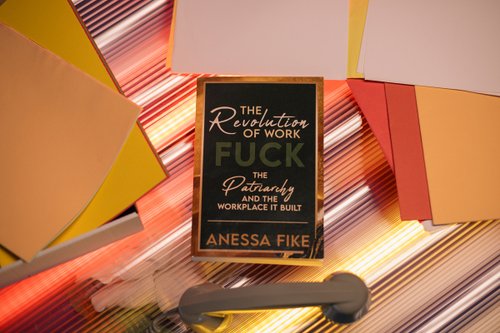

Sh*t’s broken—Here’s how we fix work for good

Built by and for a narrow few, our workplace systems are in need of a revolution.

Dec 23, 2024

What Kamala Harris’s legacy means for the future of female leadership

The US presidential elections may not have yielded triumph, but can we still count a victory for women in leadership?

Nov 06, 2024

Leadership skills: Showing confidence at work without being labeled as arrogant

While confidence is crucial, women are frequently criticized for it, often being labeled as arrogant when they display assertiveness.

Oct 22, 2024

Pathways to success: Career resources for Indigenous job hunters

Your culture is your strength! Learn how to leverage your identity to stand out in the job market, while also building a career

Oct 14, 2024

Age does matter, at work and in the White House

What we've learned from the 2024 presidential elections about aging at work.

Sep 09, 2024

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs