What comes next after years spent behind bars in the US?

Nov 14, 2023

12 mins

Journalist and translator based in Paris, France.

In the United States, 1.9 million people are behind bars — that’s the same size population as Nebraska, a state with a GDP of $161 billion. But while working Nebraskans make a minimum of $10.50 an hour, most employed US prisoners make less than $1 per hour, even though they generate an estimated $11 billion worth of goods, commodities and services.

To understand what it’s like to hold on to your career ambitions despite being locked up, Welcome to the Jungle spoke with Aaron Kinzer, a recently decarcerated writer, motivational speaker and slam poet whose work has featured in The New York Times, Newsweek and The Intercept. After spending more than a decade doing time for drug trafficking, Kinzer recounts his experience with labor exploitation, prison strikes, struggling to land a job upon release and why work is about so much more than making money.

How long you were in for, and what is your status now?

I went in in 2010. I was sentenced to 15 years, of which I served 13 years and two months. I’m currently on federal supervised release, or probation. I had an ankle monitor on for about two months. I just got it cut off in August and became basically a free man, other than the probationary period of just making sure I don’t get in trouble and maintain a steady job.

I’m scheduled to be on probation for eight years. However, I really don’t believe I’m going to do the whole eight years of probation — you can petition the courts to get early release. But they can’t just cut you loose for no reason. So I’m in the process of creating reasons. I’m building my resume up with volunteerism and community activism, and using my story to affect the youth and other communities. So once I build up a healthy catalog of work history and initiatives I’ve taken, then I can go back to the courts with a petition.

Does probation affect your employment chances? Do you have to put it on your CV that you’re on probation?

You don’t have to, but on the day where I have to report to my parole officer, I may have to leave work early, and you want to give your employer a valid reason because they may want proof. I can’t say I’m going to the doctor because they’d want a doctor’s note. In my opinion, it pays more to be upfront and say, “This is my situation coming in. There may be a time where I have to leave based upon this condition. Is that okay with you?”

And usually they say “Yeah,” because, sadly enough, America has the second-largest number of prisoners in the world. There’s an overwhelmingly large number of people who are on probation, so it’s not uncommon for employers to be faced with employees who have the type of issues that I have. You know, the opioid epidemic came through and America made an attempt — as it always does — to try to punish its way out of it by incarcerating addicts and dealers alike. They created a very large class of convicted felons in this country who are on probation or in prison. So there are people who probably weren’t doing what I was doing as far as running a multi-state narcotics operation. They were just addicts who were hooked on Oxycodone (brand names include OxyContin) or Percocet. But now they’re convicted felons and they’re on probation and they’ve got to report the same way I do.

Can you tell me a bit about your current day job and how you got it?

I work at a golf cart and utility vehicle manufacturer called Club Car, headquartered in Evans, Georgia. I went through a temp service called Spherion, so I’m an employee of the temp service and not Club Car. I’m hoping to become a full-time employee of Club Car over the next few weeks or so.

My previous job was through a temp service as well, and they placed me at the Marriott in Augusta, Georgia, as a special projects manager. I earned an early hire from the Marriott through good hard work and exemplifying leadership qualities. They decided to buy out my contract from the temp service and hire me as a full-time employee earlier than they normally would. But I left the Marriott because Club Car pays more on the hour, so it was a better situation. I was able to get more hours and generate more income so I could start to rebuild my life and meet some of the financial demands of the free world.

Are you feeling the crunch of those financial demands?

Yes. But I wasn’t oblivious to what normal life is like before I left prison, even though I was a drug dealer in my previous life. I still understood the responsibility of paying bills and maintaining a home and things like that. Now, I don’t have the large sums of cash that I had in my twenties when I was dealing. So the hourly wage means a lot more. Now it means everything.

How did the prison system prepare you to become part of the workforce in the outside world?

They don’t do anything. When you get to the halfway house, they give you a list of local companies who may hire you. They don’t call the companies and say, “I got a guy coming over there. He has experience.” It’s all on you to reach out and just stir up your new life the best you can.

The jobs in prison — library clerk, cafeteria, laundry — they just maintain the prison. It’s up to you, as a person, to find the resemblance to the real world and change your approach to your prison job. To tell yourself, “This is preparation for a job once I get out. This is what working is like.” You get up in the morning and you go to work. So it’s not just about the money. It’s about keeping your body and your mind mentally prepared for what you’re going to have to do once you get out.

There are also jobs for inmates provided by companies like the one I worked for, Unicor (a wholly-owned corporation of the government). They’re a public-private entity, and they sell themselves as prepping inmates for re-entry by equipping them with job skills. Yes, they do offer apprenticeships and different classes, although they don’t really advertise it. But once you’re released, there’s nothing. I can’t even list my Unicor boss as a reference on my applications . . . I was told by a supervisor that they can’t deal with us on a personal level once we’re released. [When asked to comment, Unicor responded: “Federal Bureau of Prisons’ (FBOP) formerly incarcerated individuals with Unicor experience may identify their former supervisors on resumes as a reference. If a prospective employer desires to verify the reference, they may contact our Office of General Counsel, for assistance with the verification. Additionally, Unicor facilitates an incarcerated individual reference letter initiative currently at three FBOP locations and has plans to expand the program.”]

So how did you find these temp agency jobs?

Well, it’s known that temp agencies hire felons first. There was another guy in the halfway house who told me that he was working at Car Club and that he got the job through Spherion. So I learned about it through word of mouth. But it’s understood in the American workforce that temp agencies are the go-between so that the Fortune 500 companies don’t have to take the risk of a criminal returning to criminal behavior, or face the social backlash of actually hiring criminals to work for them — because they didn’t hire me, the temp service hired me. So they know they can still get the benefits of my labor and not face any potential backlash by being affiliated with me.

Tell me a bit about your professional background?

As a writer, I started writing when I was incarcerated, around 2019. I’ve always been creative with my words, and I was raised with people who made sure that I understood how to speak properly. I haven’t gone to writing school. Nor have I ever received any formal training related to journalism. I’d just been writing poetry and journaling throughout my whole time in prison. In 2018, I was transferred to a low-security institution in Pennsylvania and took a writing class in a continuing education course. The instructor in that class presented us with a flier from Columbia University and their campus paper, the Columbia Journal, was hosting an incarcerated writer’s initiative. I just went into my journal and took excerpts from it, cleaned it up a little bit and submitted that to Columbia, and that became my first published piece, oddly enough.

I continued searching for writing contests for prisoners, and I found organizations like the Prison Journalism Project, the Marshall Project and Empowerment Avenue Writer’s Cohort. I reached out to them and told them I have some work that I want to submit, and the rest is history.

What other work did you do while you were incarcerated?

My first job at Unicor was at a textile factory: we sewed US military combat gear. Then in 2019, when I was transferred to Pennsylvania, I assembled office furniture. Chairs, computer chairs and things like that.

I was also an orderly at the education building, and a janitor, and I worked in the kitchen as a cook. But my most fulfilling job that I had throughout my whole time was when I was a GED (general educational development) instructor at Gilmer Federal Correctional Institute in West Virginia and Butner Federal Correctional Complex in North Carolina. I was able to really see my work affect lives, and it wasn’t about the bottom line of a company or anything like that.

Why did you end up taking a job in prison?

I couldn’t stand the boredom. You’ve got to find something that stimulates your mind. You can only write so much, play so many games of chess, watch so much TV or exercise for so many hours.

Also because I needed the money. I mean, I didn’t sell drugs for fun. I grew up poor and my mother’s handicapped; she had a stroke when I was 21 years old. I come from poverty. So if you don’t work, you don’t eat. And when I went to prison, it was a financial strain on my family because I became a bill added to the electric bill, water bill, cable bill. I’m a bill because they want me to have some socks and t-shirts, snacks and soups and things that aren’t on the prison cafeteria menu. So I got a job to be as self-sufficient as possible.

Now, you know when you’re working that it’s unfair. You know that the company’s paying you a minimum of 23 cents an hour. You can work your way up over many, many years to $1.50 an hour. So you know what you’re getting paid, and there’s open discussions around, “How much does this furniture sell for?” “What is the company making off of my labor?” and you can see the profit margins. And it’s frustrating — no one wants to be taken advantage of. But I need to provide for myself. Of course I want a fair share, but they’re not offering it, and I can’t change it. So you get up and go to work, knowing that you’re being taken advantage of.

Did the prison workers ever strike against this?

You can’t really unionize, but there have been several strikes. A strike comes in the form of a mass immobilization, where no one goes to the cafeteria to eat any food. So say lunchtime rolls around and they call the Unicor factory to the cafeteria, and none of us go. We’d circulate the word beforehand and say, “Listen, man, don’t go to lunch.”

Lunch is the biggest movement of the day. It’s the prison’s legal obligation to house and feed us. Every single day of every single week of every single month in the year. It’s a mass mobilization of 1,000 to 2,000 people three times a day, so when they call Housing Unit B and no one comes out to lunch, they know there’s some type of organized demonstration taking place. That gets their attention because they want to be in control of how we move and if all the inmates begin to organize amongst themselves, that creates a threat to the power structure. So the administration comes, and first they yell and scream and threaten. And then if we hold tight, they’ll say, “Let’s negotiate a compromise. But we can’t have you all mobilizing en mass because it’s a threat to the operation of the facility,” and they basically threaten force.

It’s like any type of organized labor — just like what’s going on with the Hollywood Union and the UAW United Auto Workers strikes. Any time the workers are organizing amongst themselves, that’s the only time they get the attention of the national media. It’s the same thing in a prison analogy, except in prison they can come behind closed doors and use deadly force to reassert order. That’s what doesn’t get seen by national media.

So we attempted to do things like that when I was there, but, sadly, there’s not a lot of people who are dedicated to the change. You may have 20% of guys who were dead set on standing up for what’s right, but then the other 80% say, “Listen, I don’t care. I get out in a year.” It’s hard to organize a strike when you don’t have people who are dedicated to the mission.

But I imagine these strikes have a very low chance of making an impact as it’s up to the federal government to raise Unicor’s wages anyway

Exactly. This is the struggle of rookie organizers, for lack of a better word. People who are passionate but uninformed about the issues and don’t have access to more information. So you just lash out and try to rattle any cage before you realize that your efforts are misplaced and you’ve got to redirect them to Capitol Hill. But the non-inmate management staff at Unicor, they don’t set the rates. They’re also workers. They’re unionized as well.

Me and some guys sent a letter to several politicians petitioning Congress to raise the pay scale of Unicor employees because it’s been the same since the 1980s. And with inflation, the cost of prison goods have gone up. So we’re paying higher prices for our deodorant or toothpaste or allergy medications. And Unicor is making lots of money. In 2022, they made over $380 million in net sales. Our cost of living as an inmate has gone up, but our wages haven’t gone up in 40 years. We never got any response back, although I don’t know what the word is now that I’ve left.

Are there prisoners who don’t want to work?

Several. The majority don’t work. There’s only so many jobs. You got 10 guys that work in laundry, you might have 50 guys total that work in the cafeteria. A Unicor factory might employ 100 people, tops. [The Unicor program has a 25,000-person waitlist, according to the American Civil Liberties Union].

The thing is, I was in the federal system and the state system is a little bit different. In the state system, you get a lot more violent crime – murder, rape, assault, stuff like that. It seems to me that most crimes that make it to the federal level are financial. So you see a lot of white collar crimes, or big-time drug smuggling rings like the one I was in. So there’s a lot more money associated with those people, and they don’t need the work. They’ve got family with money or they come from good stock, so to speak. And working in prison is beneath them, or they’re just not going to do it because they’ve got a certain view of the system.

But a friend of mine, Kevin Merrill, who worked with me at Unicor, [had been convicted for his part in] a $396 million Ponzi scheme. It wasn’t about the money. Sometimes you work because you just got to maintain some routine, some kind of normal action. Just to keep your sanity because you know prison can drive you insane if you let it.

Do you think your prison jobs gave you marketable skills and qualifications?

Yeah. I learned how to form a curriculum for a class, which now I can put on my résumé when I apply for a job teaching GED classes for returning citizens. At Unicor, I learned to use the glue applicator, the spray gun and work on certain equipment that, if put in the right situation, can translate to income and employment. Those aren’t big, great opportunities, but just for general purposes, they exist.

I was a quality assurance inspector at Unicor, and that’s my job now at Club Car. Anywhere you’ve got the production of a product, there is going to be a quality assurance inspection to make sure that product meets certain standards. So weeks ago, I pitched myself to the leadership at Club Car, saying I’d had this experience in prison. And lo and behold, someone that I didn’t speak to approached me with a job opportunity telling me they’d heard about me. But everybody doesn’t have that story. That’s a fact. There is also that person in prison who just worked on the assembly line, and all he did was tighten a screw hundreds of times a week. So they can say that they were a great assembly line worker or they work well in a team, but they weren’t in an elevated position that translates to higher income. On the outside, they were just a cog in the wheel.

What was the biggest adjustment for you in terms of working outside the prison system?

The work culture. In prison, guys worked hard. They worked fast. They were diligent because all you’ve got is your work. Your reputation and your work speak for yourself. So your effort means something, you know?

Now, what I’ve noticed on the outside is that there’s no effort. I don’t think there’s a personal incentive for people to work hard. And I’m not saying backbreaking hard, but I’ve noticed that the younger generation — I’m 42 — don’t take an interest in their work or the quality of their work. I don’t think they see the big picture of what role this company plays in the national or global situation as far as being a utility vehicle manufacturer. And I don’t think the company does a good job of painting a picture to create a team attitude where someone will care and translate that to hard work. Work ethic is lacking, and sometimes it’s hard because you don’t want to break your back with a company if you don’t really know what they’re doing or if they care about you. But sometimes you just want to be known for doing quality work.

Photo: 4Life Photography for Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram to get our latest articles every day, and don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter!

More inspiration: DEI

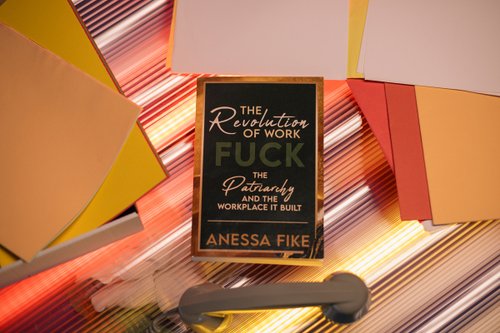

Sh*t’s broken—Here’s how we fix work for good

Built by and for a narrow few, our workplace systems are in need of a revolution.

Dec 23, 2024

What Kamala Harris’s legacy means for the future of female leadership

The US presidential elections may not have yielded triumph, but can we still count a victory for women in leadership?

Nov 06, 2024

Leadership skills: Showing confidence at work without being labeled as arrogant

While confidence is crucial, women are frequently criticized for it, often being labeled as arrogant when they display assertiveness.

Oct 22, 2024

Pathways to success: Career resources for Indigenous job hunters

Your culture is your strength! Learn how to leverage your identity to stand out in the job market, while also building a career

Oct 14, 2024

Age does matter, at work and in the White House

What we've learned from the 2024 presidential elections about aging at work.

Sep 09, 2024

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs