Picture This: Can a Drawing Help Solve Business Problems?

Oct 01, 2019

4 mins

AD

Fondateur, auteur, rédacteur @Word Shaper

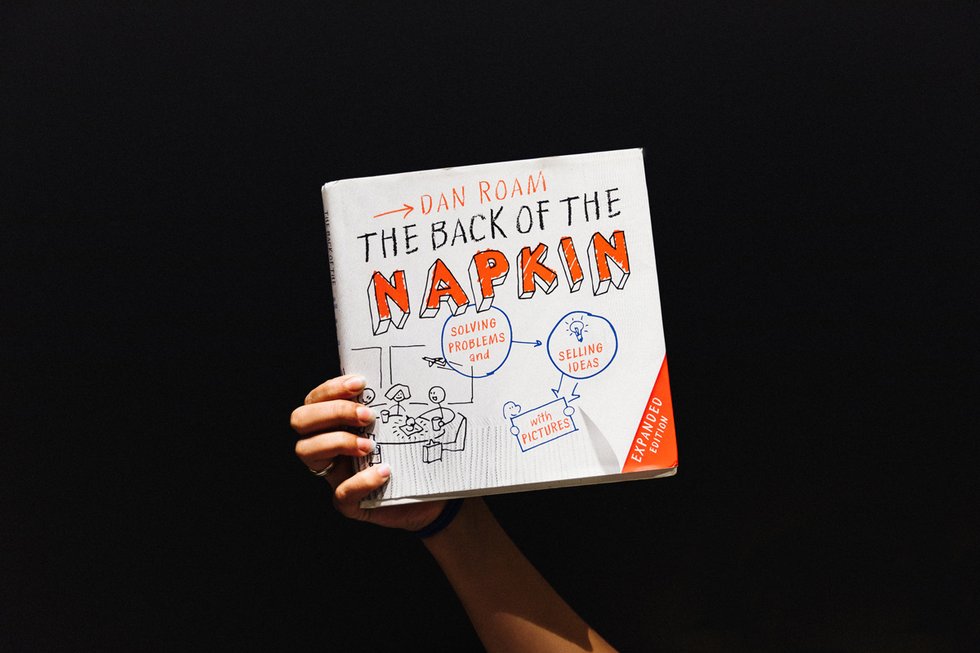

You are in a meeting and you are trying to understand your colleague’s PowerPoint presentation, but your brain isn’t making the connections—the numbers are piling up and nothing makes sense. Visual thinking specialist, Dan Roam, has some solutions for you. In his bestseller, The Back of the Napkin, he explains how a simple drawing can solve problems and express your thoughts, not only in business, but elsewhere in life too. The American author gives you practical tools to deal with any given problem, particularly for when you are developing and selling ideas. Convinced you can’t draw? Don’t worry, just follow the guide.

Draw to find, develop, and sell ideas

Whatever the business, all companies rely on the art of problem-solving—how to make money, manage teams, or meet a deadline despite supplier delays. Visual thinking is about dealing with these problems by processing visual information in a way that is separate from verbal or auditory thinking.

As Dan Roam explains in his book, you are born with the ability to visualize and build up mental pictures of ideas, even if you are otherwise convinced that you have no aptitude for it. In fact, visual thinking involves developing your sense of observation, looking at and seeing things, and then using your imagination to reinterpret them to share with others. Solving problems with images has nothing to do with being artistic and and requires no creative talent whatsoever.

According to Roam, a picture is often the easiest way to illustrate something. It’s also the best way to share an idea with a team because a drawing gets everyone behind one mode of communication. Drawings simplify things and echo the most basic concepts that are universal. They end up being a good way to encourage involvement and bring everyone together. A picture will stay in the memory of your colleagues much longer than a lengthy speech, giving them a clear vision of what they must do and why, allowing them to work more effectively.

The six questions to ask yourself

For any problem that you’d like to solve, there are six ways to deal with it. You can choose the right kind of picture depending on the type of question you want to be answered:

1. To answer the question Who/What?

Draw a portrait. Example: to define a company’s target customer profile.

2. To answer the question How much/Many?

Draw a graph. Example: to show predicted sales revenue for the year ahead.

3. To answer the question Where?

Draw a map. Example: to find the optimal solution for transporting goods from one town to another.

4. To answer the question When?

Draw a timeline. Example: to show deadlines and the company’s long-term goals.

5. To answer the question How?

Draw an organization chart. Example: to explain the roles of different teams within a company which are involved in the launch of a new product.

6. To answer the question Why?

Draw an interaction of different objects. Example: to prove to your boss that an extra week of annual vacation would have unbelievable benefits on productivity.

There’s no need to be especially original. It’s more important to choose the most coherent format for the point you’re trying to make. It’s not about drawing something realistic and/or exact; it’s about simplicity.

SQVID

As Roam explains, imagination steps in to help you see what’s inside your mind rather than what’s in front of your eyes. The author has developed a tool that encourages visual thinking called SQVID. To use it, you have to ask yourself five questions. Take the example of an apple:

- S is for “Simple or Elaborate”: do you want the apple to be represented in its simplest form, or shown in detail with its skin, stem, leaf, and color?

- Q for “Quality or Quantity”: do you wish to draw attention to the aesthetic qualities of this apple, or the objective facts about it, such as its size, weight, or density?

- V for “Vision or Execution”: do you want to simply show the apple after it’s been picked, or do you need to show the details of it’s fruition, from the tree growing, blossoming, to the apple growing into a ripened fruit?

- I for “Individual or Comparison”: do you need to just show the apple, or do you need to compare it with other fruit by drawing it alongside a pear, a banana, and a bunch of grapes?

- D for “Difference or As Is”: You can decide to show the apple as it is or to imagine what it could become, such as an apple pie or apple sauce.

While the example of an apple is a simple one, this method can be applied to any complex problem if you take the time to answer each question, one by one. The idea is to know what you need to show in order to create a picture that includes all the important information and leaves out anything irrelevant.

The 10 commandments of visual thinking

In the annex of his book, Roam shares the 10 commandments of visual thinking that sum up his theory.

1. You can solve any problem with a drawing. Whatever the nature of the problem, a drawing will always make it clearer.

2. Stop saying you don’t know how to draw. You use visual thinking to walk in a straight line, to go through doors, and to not fall over on the sidewalk.

3. Always have a notebook and pen on you.

4. Always start by drawing a circle and giving it a name. What’s most important is drawing that first line, however simple it might be.

5. Select the best picture type from the six questions Who, What, When, Where, How many and Why.

6. Give human form or characteristics to everything you draw. People respond to this, and the picture’s imperfect nature makes the problem seem more human.

7. Use every imaginable concept: the size of a picture, its orientation, and its shape are all elements that help to make sense of the problem.

8. Speak while you draw. Visual thinking doesn’t mean not talking. You can comment on what you’re drawing or erasing so your audience can better understand your train of thought.

9. Don’t focus on the quality of the picture but rather on what it’s showing.

10. Always draw a conclusion about your picture by giving it a title, an insight, or a comment. This helps to reinforce the solution found.

Roam’s book is illustrated, of course, and is based on several practical examples. His theory on visual thinking expands your horizons and makes you realize that a drawing can often simplify a problem. Pictures make finding a solution something that’s actually at the tips of your fingers—or your pens. Once you’ve taken the plunge and become accustomed to drawing pictures, solutions come more naturally and more quickly. Whether it’s at work or in your daily life, Roam’s method offers a lot of advantages, so why miss out? Grab your markers and go for it.

Photo: WTTJ

Translated by Kalin Linsberg

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook and sign up for our newsletter to receive our articles every week.

More inspiration: Productivity & tools

Goal setting: How to bounce back when you feel like a failure

The big F word ... Failure. We all face it, but here’s how to make it your secret weapon for success.

Dec 18, 2024

Productivity boost: Why mental health outshines long hours

Long hours don’t equal better work. Discover how mental health support can unlock productivity and time efficiency in the workplace.

Nov 28, 2024

10 fun ways people are using AI at work

While many use AI for basic tasks like grammar checks or voice assistants, others are finding innovative ways to spice up their work days.

Nov 05, 2024

12 Slack habits that drive us crazy

Slack is a top messaging platform, but coworkers can misuse it. Over-tagging and endless messages can make it frustrating ...

Oct 16, 2024

10 CareerTok creators you should be following

Looking for career advice? CareerTok has quick tips from real experts on interviews and job offers.

Sep 25, 2024

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs