Work Psychology : The fallacies of binary thinking

Dec 19, 2022

3 mins

Why do we procrastinate at work when we’re snowed under? Why do we imagine the worst when it comes to our jobs? Why do we work five days a week rather than three, four, or six? And who thought weekends were a good idea?

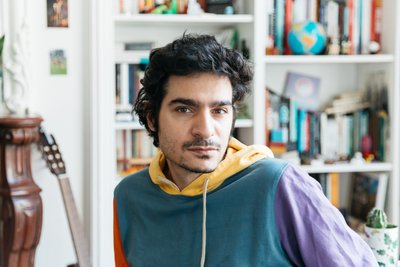

Discover Work Psychology, the series that offers you the chance to kick back and ponder existential questions from the world of work while getting one step ahead of your brain with our lab expert Albert Moukheiber.

—

Are you left-brained or right-brained? In other words, are you more drawn to science or literature? Creative arts or analytical endeavors? Do you like to write or do math?

If choosing between these options doesn’t feel quite right, it’s because it’s a false dilemma. Human beings’ brains are not actually subject to a binary state of being and the age-old way of splitting the world into two categories of people is widely regarded as an error in binary thinking.

Right-brained/left-brained: the neuromyth.

The notion of the “right brain/left brain” is an example of a neuromyth: a widespread false belief that exists about the functionality of our brains. This one in particular asserts that an individual’s personality depends on the part of the brain they use the most; thus, an artist is said to be right-brained while a scientist is supposedly more left-brained. However, this dichotomy does not actually exist.

Picking Sides

The brain is split into two parts called “hemispheres,” and some of our functions are indeed found in the brain’s left or right hemisphere. For example, in most people, the primary centers for language information processing are located in the left hemisphere. But this doesn’t mean the hemispheres have binary capacities that make a person more literary instead of scientific, or creative instead of analytical.

In actuality, oftentimes we require several skills to complete a single task. If we want to perform a jazz solo on the piano, this requires hours and hours of methodical practice—even if we’re a concert pianist. We have to understand how something works in order to be creative with it.

The opposite is also true. Testing a scientific model requires a highly developed imagination to be able to come up with an experimentation method. Let’s take Benjamin Franklin for example—an analytical scientist who was so interested in the power of lightning that he waited for a stormy night and meandered outside to capture a bolt of lightning with the help of a kite, a jar, and a key. One might not file this under the “rational approach” we usually attribute to scientific experiments.

Artists and scientists, fighting the same battle?

These days, creative work and analytical work are often split into two divisions due to our education system, which often distinguishes between the sciences and the arts. But this divide didn’t always exist. For a long time, artists were considered scientists and vice-versa, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. In fact, when all is said and done, a poet and scientist may have quite similar approaches to their work. Both are fascinated by the natural world; that is to say, the world we belong to.

Come as you are. Genuinely.

These binary divides aren’t just misleading, they’re often damaging. If someone is particularly interested in graphic design but considers themselves to be a scientific person “instead” of an artistic one, they might turn their backs on certain career paths because of the box they’ve been put in (or put themselves in). More and more companies are stating in their job adverts that they’re ‘looking for creative people.’ However, this risks sending out a sort of corporate warning: ‘If you come from a scientific background, please don’t apply.’

Human beings aren’t binary and neither are our minds. We are complex and unique beings with expansive, diverse capabilities. By dispelling the notion that we are “either this or that” instead of “this and that” we can open ourselves up to entire new worlds of professional and personal possibilities. In the words of Stephen Fry; “We are not nouns, we are verbs.”

Translated by Jamie Broadway

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: Albert Moukheiber

Doctor in neuroscience, clinical psychologist and author

What if our search for meaning at work is meaningless?

Welcome to the Jungle's psychology of work expert asks if corporate promises of meaning are merely pseudo-deep bullshit...

Oct 24, 2022

Learned helplessness: When a will doesn't provide a way

In the 1960s, two American psychologists figured out why willpower isn't always enough to turn our lives around

Oct 20, 2022

Work psychology: Don’t be afraid to voice your doubts at work

Often feeling unsure about your decisions, and yourself? Well, that might be your greatest professional asset...

Jun 29, 2022

‘Six months of working followed by two weeks’ holidays! That’s ridiculous.’

What if our balance has been wrong from the start? We spoke to Albert Moukheiber — doctor in neuroscience and clinical psychologist.

Oct 14, 2021

Psyched: is the quest for success making you unhappy?

Is professional success the sole reason for your life's satisfaction? Dr Albert Moukeiber explains why this could be harmful to your mental health.

Jul 22, 2021

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs