The motherhood penalty: Why working moms still can’t catch a break

Dec 19, 2023 - updated Feb 15, 2024

11 mins

Journalist and translator based in Paris, France.

Misty Heggeness was raised by a single mom who worked hard as a full-time secretary, yet always teetered just above the poverty threshold. “I observed my mom doing everything. And so I just assumed that women could do everything. And I grew up seeing these big gender inequities in terms of how my mom was treated,” says Heggeness, a former economist for the US Department of Labor and the Census Bureau. “You know, how difficult it was for her to be a single parent and to have an income that was just high enough above poverty that she didn’t really qualify for assistance. But it wasn’t enough for her to live comfortably.”

Heggeness is now an associate professor at the University of Kansas, where she co-directs the Kansas Population Center, which researches demographic trends in the Midwest. She’s also a go-to source on the economics of gender and care. “If you look at American men and women who are in their twenties, the gender wage gap has almost disappeared,” says Heggeness, who often publicizes how the data offers reason to hope. She’s not alone: on October 9th, 2023, economist Claudia Goldin won the Nobel Prize and, on the same day, released a working paper detailing 155 historical moments that advanced women’s rights. Pew Research recently published research showing that for well over a decade, American women aged 25 to 34 have been earning 92% of what their male counterparts make. What’s more, the gender wage gap is the narrowest on record at 84%, according to calculations by Axois, an American news website — a big win compared to the 62% recorded when the Bureau of Labor Statistics began to measure the gap in 1979.

But hitting 84% is evidence of a snail-like gain considering the gap has been sitting between 80% and 82% for the past three decades. With such progress in gender equality and so many young women maddeningly close to their fair share, what’s the hold-up? A fat chunk of research finds it coincides with the moment these women have kids.

What to expect when you’re expecting

“When we start seeing the gender wage gap really rear its head is when people start having children,” Heggeness explains. “Then, all of a sudden, we see this gap in earnings, and it’s a hit that happens to women’s earnings right at the moment of birth. It lingers throughout their entire careers.”

Before the pandemic, women’s salaries fell by $1,861 in the first quarter after they’d given birth, according to the US Census Bureau. Their pay returned to normal after the fifth quarter and continued rising – but it never caught up with their pay trajectory before they became moms. Today, Pew Research reports that while younger women have edged closer to pay parity, once they hit the 35 to 44 age range, they earn only 83% as much as men their age. It doesn’t seem like a coincidence that only 40% of 25- to 34-year-olds are moms compared to 66% of 35- to 44-year-olds. The gap widens right as the age of parenthood begins.

The motherhood penalty

The most obvious culprit behind this phenomenon is the “motherhood penalty,” aka the economic price women pay when they have children. A slew of statistics chronicle the hardships moms face in the job market. Here are just a few examples:

- Mothers are paid 75 cents for every dollar fathers make. The gap gets worse for mothers from minority groups. For every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic fathers, black mothers make 52 cents, Native American mothers make 50 cents, and Latina mothers earn 46 cents.

- Mothers are 71% more likely than fathers to stay in the same job after the birth of a child — missing promotions that their male counterparts could cash in on during maternity leave, according to the US Census Bureau.

- More than half of mothers who do switch jobs move to a different sector (64%). This probably contributes to occupational segregation: a disproportionate number of women work in lower-paying professions – such as teaching, customer service and retail – that tend to have fewer hours, giving moms more flexibility to care for their kids.

- What’s more, Goldin’s research shows that even for employees on a monthly salary, working less than 40 hours per week can keep down their pay. Given mothers’ need for flexibility, it’s no surprise that 32% of women worked less than 40 hours per week, compared to 10.5% of men in Goldin’s 2015 report. Mothers are more likely to work part-time, take longer periods of absence or leave the job market altogether.

- This is part of the reason why, in 2021, 56.1% of women participated in the labor force compared to 67.6% of men. For moms who do go back to work, this dip in professional experience often makes it harder to catch up on promotions, earn higher wages and save for retirement.

Thanks to these obstacles, even mothers who work full-time make about $17,000 less per year than fathers. Many economists think this financial punishment for moms is the main cause of the glass ceiling, as research shows that progress on both the motherhood penalty and the gender wage gap began to stagnate at the same time.

So it’s no wonder that when the pandemic hit, economists worried that women would leave the labor force in droves:

- Moms bore the brunt of managing their out-of-school children, making it hard to get work done.

- Many of the lower-paying industries that employ high numbers of women are in-person jobs that couldn’t be converted into telework.

- As fathers tend to earn more than mothers, it was a logical financial decision for heterosexual couples to send dad back to work while mom managed the kids stuck at home.

But to everyone’s surprise, the number of mothers in the labor force increased after the pandemic. “We don’t have data in front of us to accurately tell us what is going on, so we end up falling back on traditional normative thoughts,” says Heggeness. “We saw that it was crazy chaos in terms of caring for children. And when we saw that, we said, ‘Oh, who cares for children? Moms care for children. And so this is going to imply that moms are going to have a mass exodus from the workforce.’ And all the alarm bells went off.”

It turns out that mothers ran back to work much faster than non-moms, thus achieving their highest labor force participation rate on record. Heggeness believes this is, in large part, because most American families need two incomes to survive. “Working moms aren’t going out into the labor force and working to buy a pearl necklace,” she says. “Moms are working because they need to pay the bills, just like dads are working because they need to pay the bills. If you’re a parent, you have the extra somebody else in your household who depends on you for survival. That’s not the case with college-aged single women, and it’s not generally the case with women of retirement age.”

The fatherhood bonus

In another surprising twist, the Pew Research Center recently claimed that the motherhood penalty may not be the main reason the gender wage gap worsens with age. Previous studies have indicated that mothers are six times less likely to be recommended for hire than women without children and earn 5% less per child than non-moms. Yet Pew’s analysis of data from the 2022 Current Population Survey found that mothers earn pretty much the same amount as non-moms with similar levels of education, though both types of women earn less than men.

There’s a problem, however, comparing moms to women without kids: there are many reasons why a woman may not have children, and some can cause her to earn less than her peers. For example, disabled women are less likely to plan on having a child than women without disabilities, and they’re also more likely to make less money. As multiple penalties are surely at play, a more detailed analysis is needed before discounting how much motherhood contributes to the wage gap.

Nonetheless, Pew Research emphasizes another phenomenon adding to the crevice: the fatherhood bonus. Many studies show that when men become fathers, they begin to make more money and work more hours than everyone else in the labor market. This means that men without children are penalized too, as they make more money than women but only 88% of what dads earn, according to Pew. So even if all women reached wage parity with non-dads, they’d still be making less than fathers – and thus the gender gap would continue.

While Pew suggests that the fatherhood bonus is a bigger driver of the gender wage gap than the motherhood penalty, the two trends probably work in tandem. The majority of families in the US are heterosexualcouples, so if dads are spending more time on the job and scooping up more bonuses for this hard work, who is sacrificing those extra paid hours and possible promotions to make sure the kids are alright?

The culture war

We tend to assume the gender wage gap is due to sexist workplace norms. While those seemingly outdated biases certainly haven’t disappeared, the focus on toxic work culture tends to overshadow another enormous obstacle to pay parity: what happens at home.

In May 2023, economists from Columbia University and the Brazil Institute of Labor Economics published new research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) showing that when a mother in the US works for a company with more than 75% women employees, she still incurs a penalty. The penalty actually grows faster for mothers at companies run by women leaders. Even women who are the breadwinners of the family see a big drop in earnings, losing 60% of their pre-childbirth pay compared to their male partners. The US’s notorious lack of paid maternity leave seems to explain these findings – except that both Germany and Austria have generous paid parental leave and large motherhood penalties. If mothers are losing out despite all these empowering work arrangements, the call must literally be coming from inside the house.

“If we’re really going to reduce the motherhood penalty, we need to focus not only on what corporations and employers can do, but also what we can do within our homes in terms of reframing the workload,” says Heggeness. The authors of the PNAS report agree, saying that cultural norms around childcare greatly affect the gender wage gap. “Ultimately, the traditional thinking is that child care by default is the responsibility of the mother,” one of the researchers told The Washington Post. He notes that in Sweden, which has a lower motherhood penalty, he sees as many fathers as mothers on the playgrounds – a “striking difference” from what he’s observed in New York City.

We’ve come a long way in realizing that women are as professionally capable as men, but we’ve yet to twig that men are just as domestically competent as women. The problem isn’t always machismo, however, as dads are spending three times as long on childcare than they did 50 years ago – although the majority feel like they’re still not spending enough time with their kids. Factors hampering their involvement include more pressure to return to work than mothers and less confidence in their parenting abilities.

Even women without children feel this cultural burn: More than half of unpaid elder care is done by women, 15% more women do housework than men and even women who earn more than their husbands do more chores. Of course, this also contributes to the gender wage gap widening over time, as parents age and home projects pile up.

Could WFH help?

The massive shift to telework was hailed as a solution to the work-life balance woes of American moms. Simply getting rid of a commute is estimated to save workers around two hours per week, which are generally spent on paid work or household duties — giving mothers more time to make money or care for their kids. Sabrina Pabilonia, an economist at the Bureau of Labor Statistics who researches the work-life balance of work-from-home (WFH) parents, also points out that fully-remote policies allow mothers to “move near their family, who may be able to help out with caregiving for children and allow women to devote more time to their careers.”

The WFH boom also led to fathers helping out more around the house. Pabilonia’s research found that during the pandemic, dads working from home alone engaged in more childcare and household chores than their partners at the office, which decreased the gender care gap. Pabilonia believes if this trend continues, it could “somewhat alleviate the motherhood penalty.”

Yet WFH mothers have encountered pitfalls. Another report co-authored by Pabilonia found that during the pandemic, WFH mothers mixed paid work and child supervision more than WFH fathers, and this multitasking can lead to less productivity. In fact, these constant interruptions during work hours cost women an estimated 9% in wages. “You’re doing a task and you’re focused, right? And then all of a sudden you get interrupted, and you have to regroup and get back to it,” says Pabilonia. “Potentially, you could have lost productivity.” While remote employees generally make more than their on-site counterparts, the report found this wage premium is lower for mothers of young children than for other WFH groups — and childcare interruptions may be one reason why.

The fact that WFH mothers spent more time on secondary childcare — watching the kids while doing something else — indicates that women still “have the primary responsibility for the children, or that the children view the mother as the primary caregiver,” says Pabilonia. When children need something, she says, they may tend to run to their mothers first despite both parents working at home. This could be more than just a biological reaction; a recent study from Tufts, Syracuse and Brigham Young found that schools are 1.4 times more likely to call mothers than fathers even if both parents indicate they’re equally available.

So what’s the solution?

“Childcare, childcare, childcare – and then policies that encourage and normalize dads taking on care activities,” says Heggeness. She believes remote work will only help mothers if someone else looks after the little ones so moms can stay focused on their paid labor.

But to aid politicians and company leaders in crafting policies around affordable daycare, paid parental leave and incentivizing fathers’ involvement at home, we need more statistics to understand what’s going on. For example, a working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows how the gender wage gap began to stall in the 1980s at the same time as a well-meaning federal policy was put into place that gave workers the right to unpaid parental leave. Since then, more mothers have called in absent than fathers, making less cash and missing potential opportunities to climb the pay scale.

“In my opinion, part of the reason we don’t do a good job in the US creating systems that provide support is because we don’t produce the right sorts of data and indicators that would help inform changes,” says Heggeness. She points to the roughly 25% of prime-age women (25 to 54) with school-age children who don’t have paid work. “What do we know about those women?” she says. “Are they choosing not to work because they just want to have one [unpaid] job, which is the economic activity involved in raising children? Or would they prefer to work, but can’t because they can’t afford childcare?”

While raising children isn’t remunerated, it does generate future taxpayers. What’s more, childcare, cooking, cleaning and other chores are services that can become paid jobs when people are wealthy enough to delegate them. With this logic in mind, Heggeness advocates for more research into the unpaid work happening within America’s homes and incorporating it into how we think about our country’s economy. She’s currently building The Care Board, a dashboard for care work statistics funded by a $762,000 grant from the Alfred P Sloan Foundation, which is scheduled to be launched in 2024.

Heggeness argues that household production has long been considered “girly statistics,” as the economists who created the concept of gross domestic product (GDP) after the Second World War purposely chose to calculate only goods and services produced outside the home, which was a male-dominated area. But from changing diapers to fixing a leak, household work involves everyone, and measuring these activities could provide a more accurate picture of huge economic issues such as burnout and wealth inequality. Above all, it will help society recognize that women like Heggeness’s mom are working far longer hours than they’re being paid for and are contributing far more to the economy than is obvious.

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram to get our latest articles every day, and don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter!

More inspiration: DEI

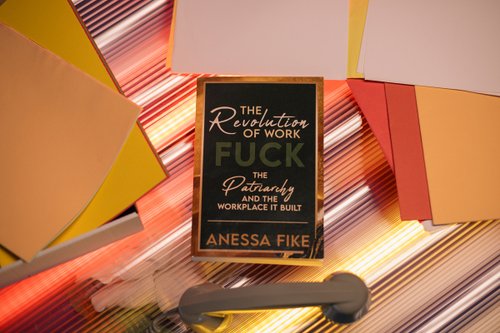

Sh*t’s broken—Here’s how we fix work for good

Built by and for a narrow few, our workplace systems are in need of a revolution.

Dec 23, 2024

What Kamala Harris’s legacy means for the future of female leadership

The US presidential elections may not have yielded triumph, but can we still count a victory for women in leadership?

Nov 06, 2024

Leadership skills: Showing confidence at work without being labeled as arrogant

While confidence is crucial, women are frequently criticized for it, often being labeled as arrogant when they display assertiveness.

Oct 22, 2024

Pathways to success: Career resources for Indigenous job hunters

Your culture is your strength! Learn how to leverage your identity to stand out in the job market, while also building a career

Oct 14, 2024

Age does matter, at work and in the White House

What we've learned from the 2024 presidential elections about aging at work.

Sep 09, 2024

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs