The EQ obsession: does it help or harm neurodivergent workers?

15 sept 2021

5 min

Translator and writer

“If it does not include our perspective, how emotionally intelligent is it really?”—Christine Bélanger

Emotional intelligence has been a darling of the self-help movement for more than 25 years—and has lately taken the professional world by storm. Today EI is referenced in a wide range of workplace practices, from job interviews to performance reviews. But what about neurodiverse professionals? Could having a neurodivergent brain put you at an emotional disadvantage? And do EI-based practices make the workplace more inclusive or are they potentially discriminatory? We spoke to professionals from the neurodivergent community for their take on the subject.

A distinctly human intelligence

The concept of emotional intelligence (EI) is defined as the ability to recognize, understand and manage your own emotions. It is also referred to as EQ (emotional quotient) and folds neatly into comparisons with the IQ of raw intellect.

EI owes much of its popularity to advances in smart technology. Putting emotions on a par with—and sometimes even higher than—intellect helps assuage the all-too-human fear of being replaced by machines.

A quarter of a century ago, Daniel Goleman helped bring the concept into the mainstream with his book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. In the introduction to the 25th-anniversary edition, Goleman writes: “As we get further into the age of the smart machine, it is likely that sensing and managing emotions, particularly in relationships, will remain one type of intelligence that stymies AI. This means that people and jobs involving EI are safe from being taken over by machines.”

The World Economic Forum made a similar prediction in its 2016 report The Future of Jobs. EI came out as one of the top 10 skills to have by 2020, primarily as a response to the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its impact on global employment trends. That was before Covid-19. The widespread insecurity caused by the global pandemic has shifted the continuing revolution into an even higher gear.

EQ before IQ

While it may be a sure path to staying relevant in the job market of tomorrow, emotional intelligence is equally important for anyone looking to build a career now. In a 2011 survey of 2,662 US hiring managers, the employment website CareerBuilder found that 71% valued EQ over IQ. More recently, a 2019 study conducted by the UK recruitment agency Michael Page found half of employers saying EI was an increasingly important skill for candidates to possess, with 45% placing it above work experience and higher education.

This focus on emotional intelligence could put neurodivergent professionals at a disadvantage and may, in some cases, even be discriminatory. Some conditions, such as ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, are associated with emotion dysregulation and social deficits. And as difficult as managing these symptoms can be in everyday life—both professional and personal—it can be an added stress to live with the stigma of low emotional intelligence.

Christine Bélanger, from Toronto, Canada, read Goleman’s book before she was officially diagnosed. She was looking for answers to why she felt different—and some of that was down to how she experienced emotions. “I became familiar with EQ because I thought I was lacking in it. That’s a message that we get our entire lives,” she says. “I looked at it as a structure to try to help me understand other humans because I thought I was at fault.”

Father knows best

After spending a significant part of her 20-year career in business development acting neurotypical, Bélanger eventually chose to claim her Tourettic identity and has since become a disability advocate. Today, she’s an R&D consultant for workplace inclusion programs.

Through both her experience and her advocacy work, Bélanger’s thinking about emotional intelligence shifted. “In retrospect, by trying to understand EQ, I was trying to accommodate the world around me,” she says. “When you stop accommodating the world, all of a sudden you find out who you really are under all those layers of masking.” She thinks emotional intelligence could use a solid dose of “critical thinking” to become inclusive and up-to-date in today’s workplace. “It’s valid as a concept,” says Bélanger, “but if it does not include our perspective, how emotionally intelligent is it really?”

Her first impression of Goleman’s approach to emotional intelligence was that it seemed somewhat paternalistic. “The concept of EQ itself is great, but it’s moralistic. It’s good as a guideline, but it’s very ‘Father knows best’. It favors neurotypicality and neuro-normative standards,” she says.

A guide for understanding

“The concept [of emotional intelligence], as it’s applied right now, has done a great disservice to neurodivergent people”—Rachel Worsley

Rachel Worsley, from Queensland, Australia, is the founder and CEO of Neurodiversity Media. She, too, has mixed feelings about how emotional intelligence is used in the workplace today. “In general, emotional intelligence is good for everybody to learn as a skill—collectively, everybody benefits,” she says. “But the concept, as it’s applied right now, has done a great disservice to neurodivergent people.” She’s hoping to shift the narrative by providing accessible resources for neurodivergent professionals and employers.

She, too, has mixed feelings about how emotional intelligence is used in the workplace today. “In general, emotional intelligence is good for everybody to learn as a skill—collectively, everybody benefits,” she says. “But the concept, as it’s applied right now, has done a great disservice to neurodivergent people.” She’s hoping to shift the narrative by providing accessible resources for neurodivergent professionals and employers.

Before launching her own company, Worsley held a variety of roles in marketing, journalism, law, creative writing, and community radio. Like Bélanger, she also felt different. Worsley believes that the challenges involved in managing and expressing your emotions in a neurotypical workplace can cause undue job stress for some neurodivergent employees.

The basic premise should be to support different ways of feeling and managing emotions. That’s where neurotypical standards of emotional intelligence are weakest. “The problem is not the standard itself,” she says. “It’s the terrible inflexibility of how the standard is applied to force people to conform, rather than being seen as a guide for understanding.”

A narrow vision of leadership

Rachel Morgan-Trimmer is a neurodiversity consultant, trainer, and speaker from Manchester in the UK. Before launching her own business, she worked in traditional office environments. Back then, she didn’t know she was autistic, but when certain colleagues told her she was “blunt”, it didn’t always sound like a compliment. They might have chosen a more helpful—or less euphemistic—word to describe how they were feeling. Morgan-Trimmer believes that anyone with “average emotional intelligence” would benefit from developing the skill. “In my experience, somebody who is emotionally intelligent is a good person to be around because they’re not making assumptions about me,” she says.

At the same time, she finds current standards of emotional intelligence to be limited in scope, especially when it comes to leadership. In the business of executive coaching, for example, high EQ is often a coveted skill. And when recently designing a course for neurodiverse managers, Morgan-Trimmer struggled to find relevant material. She was frustrated, but not surprised. “We generally have a very narrow vision of what a leader should be and what they should look like,” she says. “People don’t expect neurodiverse individuals to be in leadership positions.”

There needs to be a conversation

Michelle Harris Price, from San Diego, in the USA, worked her way into a leadership position before she knew she had ADHD. She had a successful 19-year career working at UC San Diego Health, the city’s only teaching hospital. Price always felt different: from a young age, she was singled out as intellectually gifted. “I hated it, as it pointed me out when I didn’t want to be pointed out. I mean, I just didn’t want to be any weirder than I already felt,” she says.

Like Bélanger, Price used the concept of emotional intelligence to help make sense of the world around her. “I learned early on that I was really interested in anything that could tell me about myself and how I was,” she says. “I felt that the more I understood myself, the more I understood other people.”

Looking back, Price suspects that building her career without the label of ADHD was good in many ways. “I ended up rising through the ranks at work when I discovered what I was good at—which literally leveraged my neurodiversity,” she says.

At the same time, Price believes current high EQ standards would benefit from exposure to other ways of experiencing, expressing, and managing emotions. “It feels like emotional intelligence is being judged by someone who is not neurodivergent,” she says. “There needs to be a conversation about it. There’s no conversation right now. That’s the flip side of emotional intelligence.”

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

Más inspiración: DEI

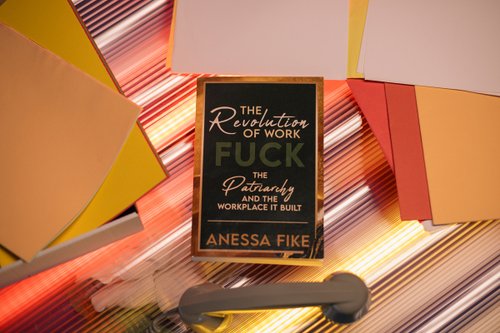

Sh*t’s broken—Here’s how we fix work for good

Built by and for a narrow few, our workplace systems are in need of a revolution.

23 dic 2024

What Kamala Harris’s legacy means for the future of female leadership

The US presidential elections may not have yielded triumph, but can we still count a victory for women in leadership?

06 nov 2024

Leadership skills: Showing confidence at work without being labeled as arrogant

While confidence is crucial, women are frequently criticized for it, often being labeled as arrogant when they display assertiveness.

22 oct 2024

Pathways to success: Career resources for Indigenous job hunters

Your culture is your strength! Learn how to leverage your identity to stand out in the job market, while also building a career

14 oct 2024

Age does matter, at work and in the White House

What we've learned from the 2024 presidential elections about aging at work.

09 sept 2024

¿Estás buscando tu próxima oportunidad laboral?

Más de 200.000 candidatos han encontrado trabajo en Welcome to the Jungle

Explorar ofertas