‘Working as an ethologist is one way to take action for a better world’

Feb 08, 2022

11 mins

Editorial Manager - Modern Work @ Welcome to the Jungle

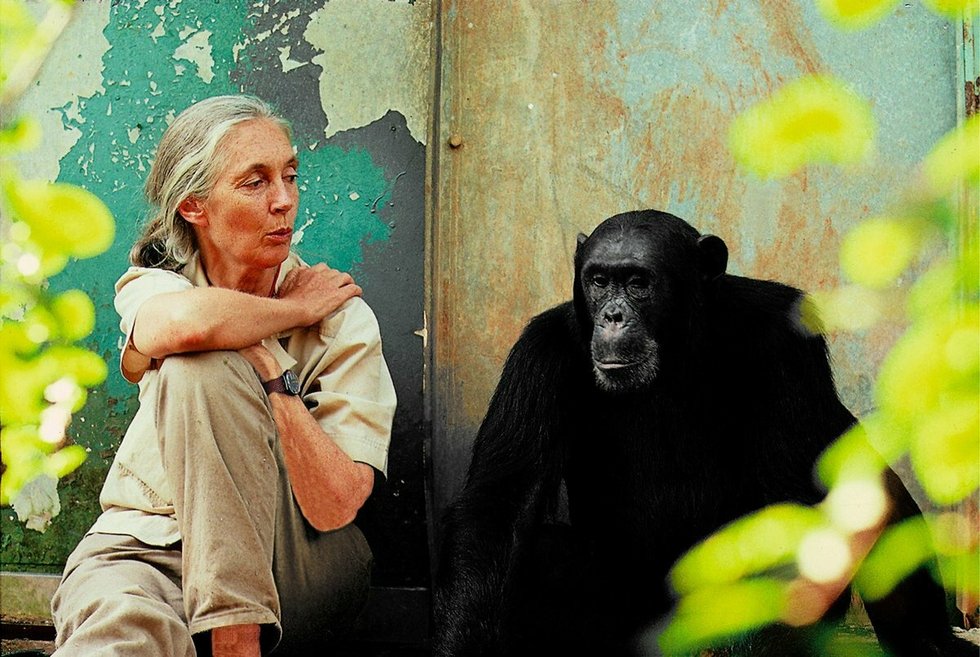

Jane Goodall is the world’s most famous ethologist. The 90-year-old scientist has revolutionized our understanding of great apes, and has fought relentlessly to preserve life. Through the Jane Goodall Institute, numerous preservation programs, her books—the latest of which, The Book of Hope, was published in October 2021—and conferences around the world, Goodall continues to spread her stories filled with hope. Her work continues despite the pandemic, which forced her to navigate digital activism via virtual speeches and the launch of a podcast. We were lucky enough to be able to interview the ever-passionate Goodall.

At 87, you have had an impressive career. How would you describe it in a few sentences?

I don’t really think of it as a “career.” I had a dream and I made it a reality. I have always loved animals and my dream was to go and see them in Africa. Fate has tied my life to chimpanzees, and I have dedicated my life to knowing and protecting them. Thanks to my work in this field I was able to see how mankind was destroying the natural habitats of wild animals, by deforestation, agriculture and the like. Everything in the living world is linked. Between humans, other animals and nature, we form a “tapestry of life” where each segment is important. This is why I decided to act. Down the line, people joined me and now we all work together at the Jane Goodall Institute.

What would you say to someone meeting you for the first time if they asked what you do for a living?

In life, I consider myself an activist, telling stories that speak to the heart. I carry a message of hope. I would say that I am a “hope broker!”

You are the most famous ethologist in the world. How do you feel about this fame and how has it affected your life?

Fame is relative. If it can help me to touch people’s hearts and at the same time encourage them to take action, that’s great. But to be honest it doesn’t have a huge impact on my everyday life.

The reality of your job is not widely understood by the general public yet nonetheless still manages to make people of all ages dream. How do you explain that?

I have never considered my activity or my life as a “profession.” People today are much more aware of animal protection, the fall in biodiversity, the sixth mass extinction and climate change. There is a growing acceptance of the fact that humans are an integral part of the animal kingdom. A growing number of people are aware of the issues at stake and want to act. But so much more needs to be done! We can all do our part, by adopting ethical behaviors day by day. Ask yourself: “Was this thing I want to buy created without involving child labor or animal testing?” “Does the person I’m voting for share my values?” Working as an ethologist is one way, among others, to take action for a better world. It’s worth thinking about.

How can people become ethologists today and what tips would you give them?

Students can study animal personality, intelligence and emotions. I could not have studied any of these because they were not supposed to exist. Scientists are beginning to understand that we are part of the animal kingdom, but there are still small pockets of resistance. For example, people who work in animal research labs, in those horrible factory farms or in slaughterhouses don’t want to think that animals can feel. And yet…

Being an ethologist requires curiosity and patience. To have an open mind, without prejudice. To love animals, to respect them. I was lucky enough to be able to become an ethologist without any prior scientific training. I am not sure that this is still possible today. Both the relevant courses and the job itself have changed a lot.

Relevant courses have become more adapted too. At the time (we’re talking 60 years ago), fieldwork observing wild chimpanzees in their natural environment had never been done. Not by anyone. The fact that I was a woman did not help convince the ethologists at the time that human beings are not the only species with personality, spirit and emotion. That’s still the case today I think, but much less so. Thankfully.

It was during a trip in 1957 that you discovered wildlife and met the renowned paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey. Was he the one who sparked your passion?

I had always dreamed of going to Africa and seeing the wild animals. The Tarzan book really spoke to me and I wanted to be his Jane! When a friend asked me to come and visit her in Africa, I immediately accepted the invitation. I went and had the great fortune to meet the famous paleontologist Louis Leakey. Finally, the boring secretarial studies I had done were of use to me: he was looking for a secretary and I was able to work with him. What made a huge difference was the fact that he trusted me. He saw how passionate I was, that I had read so many books. He was the one who suggested that I go and observe chimpanzees in the field. He gave me a chance even though I had no experience, no training. It was because he found me passionate, curious and patient. I am very grateful to him.

In 1960, you spent several months in the forest at Gombe (in Tanzania), in order to get as close as possible to the chimpanzees. How were you so sure that this was the best way to do your job, especially when no one else thought that?

Actually, I used the same techniques I used to observe animals near my home as a child: sit down, be patient, don’t get too close too quickly. But it was hard because initially the study was only supposed to last six months. Can you imagine how difficult it was for a young girl without a science degree to do something as strange as living in a forest, almost alone with these animals we knew so little about? I knew that in time I would gain the trust of the chimpanzees, but would I have the time? Leakey had secured funding for a few months. Time was of the essence.

At first, they would run away from me. Weeks turned into months, and finally, after four months, one chimpanzee was no longer afraid of the “hairless white monkey” that I was. He was the one I saw, through my binoculars, making and using a tool to catch termites. I wasn’t too surprised, because I had studied chimpanzee behavior in captivity—but I knew that science believed that only humans used and made tools.

That observation led me to National Geographic, and they said, “OK, we’ll support you in your research.” They sent Hugo van Lawick, a photographer and director, to film my research. Many scientists didn’t want to believe this discovery. One of them even said that I must have taught it to the chimpanzees. After seeing Hugo’s film and reading all my descriptions of their behavior, the scientists were forced to change their minds.

Generally speaking, I was often confronted with people who thought that what I was doing was not at all appropriate and questioned my procedures, my ways of doing things. They even questioned my results. For example, I gave each chimpanzee a name, not a number. The scientists at the time thought that this would distort my results, that I should not show empathy but remain cold and distant. But what’s important is to do things the way you feel is right.

In the 1980s, you moved from research to activism. Is being an activist a profession, a state of mind, a passion, or a simple necessity? How did you find yourself in this role at the time and how does it affect you today?

I lived my best years in the forest, with animals. I was really happy there. In the late 1980s, I became aware of what was happening in Africa, of the reduction and destruction of the natural habitats of wild animals. I flew over Gombe National Park in Tanzania. It was part of this great belt of equatorial forest that extended to the west coast. At the time it was a small island of forest, surrounded by completely bare hills. The agricultural land was overused and became infertile. The inhabitants cut down trees, even on the steep slopes, because they had to survive. They were too poor to buy food elsewhere and they needed the wood for heat. I realized that if we can’t help these people find ways to live without destroying their environment, we can’t save the chimpanzees, the forest or anything else. So becoming an activist became an obvious choice.

And so we started TACARE, which helps people to reconnect with a sustainable way of life. With this educational program, we raise awareness of nature conservation among adults and children in Tanzania, so that they too can contribute towards this important work. People, other animals and nature are all connected. It is important to work on all three simultaneously for long-term and sustainable results.

You founded the Jane Goodall Institute (currently working in 24 countries), and the Roots and Shoots program, which enables 100,000 young people around the world to make a change. What are you most proud of today?

To have succeeded in changing the way science looks at animals. Previously, it was considered that there was an impassable gap between them and us. By showing how much chimpanzees resemble us, my work has paved the way for the study of all sorts of species whose great intelligence is now known: crows, whales, octopuses and more. It’s a step forward that I hope will contribute to making us more respectful and caring toward animals. All I wanted to do at the time was to discover the world, to study chimpanzees. I’m proud to have contributed to changing attitudes towards animals. That is very important to me.

Another thing I’m proud of is that I started the program you mentioned, Roots and Shoots, which is one of the only ones to combine humanitarianism and environmental advocacy. Young people understand that there are things that are much more important than skin color, culture, religion, language and the food you eat. It’s that we are all human beings. It stays with them all their lives, and children influence their parents in this direction. All this creates massive changes in the world.

As an activist, you are known for your calmness, your “soft power.” What are your “weapons” to defend your cause: that of the chimpanzees and nature as a whole?

All living things are facing threats that we all know today. We must take action immediately to slow down global warming and to stop the disappearance of plant and animal species. It’s the only way forward. If we wait too long, it will be too late. So everyone needs to be aware of the challenges. Reducing poverty, of course: when poverty is present, we cut down the last tree to grow our food. We catch the last fish to feed our family. In the city, we buy what is cheapest—we cannot afford the luxury of choosing an ethically produced product. Our second challenge is to reduce the lifestyle of the rich, which is unsustainable for the planet. Let’s face it: many people have far more than they need. Our third challenge is to eliminate corruption. Good governance and honest leadership are necessary to solve environmental and social problems of this magnitude.

Finally, we must address the problem of population growth. There are now more than seven billion people on the planet, and in many areas we have already consumed more resources than nature can produce to replace them. By 2050, that number is expected to reach 10 billion. To continue as we are without change would be to sign the death warrant of life on Earth as we know it.

We need to get the message out. We need to get our heads and hearts in line: we need to convince everyone to take action now.

You often say you believe in the power of “true” stories, and that you want to touch the hearts of your opponents through storytelling. Why is that, and does it work?

When I meet someone who disagrees with me, one thing I never do is confront them, especially aggressively. If you want someone to change their way of thinking, there is no point arguing with them. You have to get to the heart, and storytelling is the best way to do that. I’ve lived long enough to know that there is usually an appropriate story for almost every situation! I’ve found that stories speak to the heart much more than raw data or patterns. When they’re told well, people remember the message, even if they forget the details.

“If you want someone to change their way of thinking, there is no point arguing with them. You have to get to the heart, and storytelling is the best way to do that.”

Before the pandemic, you spent the majority of your time traveling. Do you miss it? After a year and a half being confined to your family home in Bournemouth, in England, it looks like you’ve been working from home like everyone else! What do you think of it?

I was driving to the airport to give a talk at the United Nations in Brussels when I was told to stop and go home. That was the last time I tried to travel anywhere—except to get vaccinated!

At first, I was frustrated and angry. I was used to traveling 300 days a year all over the world and speaking to people, to auditoriums of 10,000-15,000. All of a sudden I’m stuck here in the UK, and I thought, “There’s not much point in being angry and frustrated.” So we decided to “build” a virtual Jane, and this “digital” Jane has managed to reach millions of people in many more countries than if I had done my normal, in-person visits. I give talks and I produce a podcast called Hopecast. It must be working because I have been told that the people listening are moved by the message I’m sending out.

I am at home in England, in the house I grew up in. I am surrounded by things from my childhood. The trees I used to climb are there in the garden. Every day I have my sandwich under a special tree and I am joined by a robin and blackbirds. I watch nature. Of course, there are times that I get sad or down on myself, but I try to turn it around by thinking, “Well, OK, I’m going to do something about this.” I live in the moment and do my best to take action from where I am.

In October 2021 you published your 22nd book, The Book of Hope. What is it about and why did you choose this title? Does it reflect the purpose of your career?

We live in such dark times. Everywhere you look, the climate, the politics, it’s pretty dark. And if people are losing hope, then we might as well give up, because if you don’t have hope, what’s the point? Eat, drink and have fun, because tomorrow we die? But it was this hope that allowed us humans to emerge from the time when, even though it took a lot of work to make a stone tool, there was hope that this stone tool would help you find your next meal. To go out and hunt large, dangerous animals, there had to be hope that you would succeed.

So I think hope is part of our human evolution. A force that has brought us to where we are today. But because there is so much darkness in the world, it is more important than ever to try to keep that flame of hope alive, especially for young people.

In the book, we understand that you place a lot of hope in the younger generation. Why is that? What do you want to tell them, and what can they do today to support your efforts?

It is important for young people to get involved. It can be in the context of their work, either directly if it contributes to a better world, or indirectly by moving with their company towards change. Small gestures count. At the Jane Goodall Institute, for example, we have a campaign called The Forest Is Calling, which encourages people to recycle their old cell phones and raises awareness about digital pollution. This can be a great first step.

Each of us can get involved as a volunteer, whether it’s at the Jane Goodall Institute or elsewhere. We can all give our time, help in the field or at a computer, by relaying information to our friends or on social networks. Don’t hesitate to contact the Jane Goodall Institute. They do a great job and have a team of very dedicated volunteers.

You often mention specific changes that anyone can make—such as becoming vegetarian—but what should companies do?

Companies have an important role to play. So do individuals and national and international public authorities. They are one piece of the puzzle and we have to work together to make changes. Companies have a responsibility to do their part. Internally, by managing their office operations in the most sustainable way possible, considering digital pollution, the equipment available, and how people get to work. But also by involving their employees, by encouraging them to act, by committing themselves to causes.

It’s a great way to engage your employees, your customers and your suppliers. They will be proud to pull together on important work like this. It creates positive dynamics. By helping associations, whether it be the Jane Goodall Institute or others, your impact is multiplied. That’s important too.

Is it true that you are going to start traveling again in 2022, though less than before? Is working for future generations the thing that drives you?

I’m doing my part.

Translated by Kim Cunningham

Photos: Michael Neugebauer, X Frame Films, Jane Goodall Institute, Derek Bryceson

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook on LinkedIn and on Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: Inspiring profiles

Be real, get ahead: The power of authenticity in your career

Pabel Martinez shares insights on how to allow yourself to be yourself, find your voice, and deconstruct stereotypes at work.

Apr 25, 2024

The professionalism paradox: Navigating bias and authenticity with Pabel Martinez

Pabel Martinez challenges the conventional norms of professionalism by unraveling the complexities of workplace discrimination.

Mar 11, 2024

How play can make you happy, creative and productive at work

Work-life balance usually means separating work and play, but it might be a better marriage than you think...

Nov 07, 2023

Project Street Vet: Caring for the unseen paws of Skid Row

Providing vet-to-pet care in some of California's largest homeless communities, Dr. Kwane Stewart shares the ups and downs of his remarkable work.

Aug 29, 2023

Girls learn how to have fun – and funds – by investing

A Danish trio is fighting gender inequality... on the stock market. We had a chat with one of the co-authors of the book Girls Just wanna Have Funds

Jan 30, 2023

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job opportunity?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs