WIDE ANGLE | To infinity and beyond

29 nov. 2021

6min

Journalist & Content Manager

Photographe chez Welcome to the Jungle

Welcome to the depths of the Earth, where scientists collide particles to penetrate matter and answer the thousand-proton question: exactly where do we come from? If you think that sounds exciting, stick with us. Laetitia Bardo, head of safety for the ATLAS experiment at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), will take us on a tour that is truly out of this world. Her job is to ensure the safety of some 3,000 scientists working on ATLAS, the largest particle detector ever built. Hers is a high-flying role in what remains a male-dominated field.

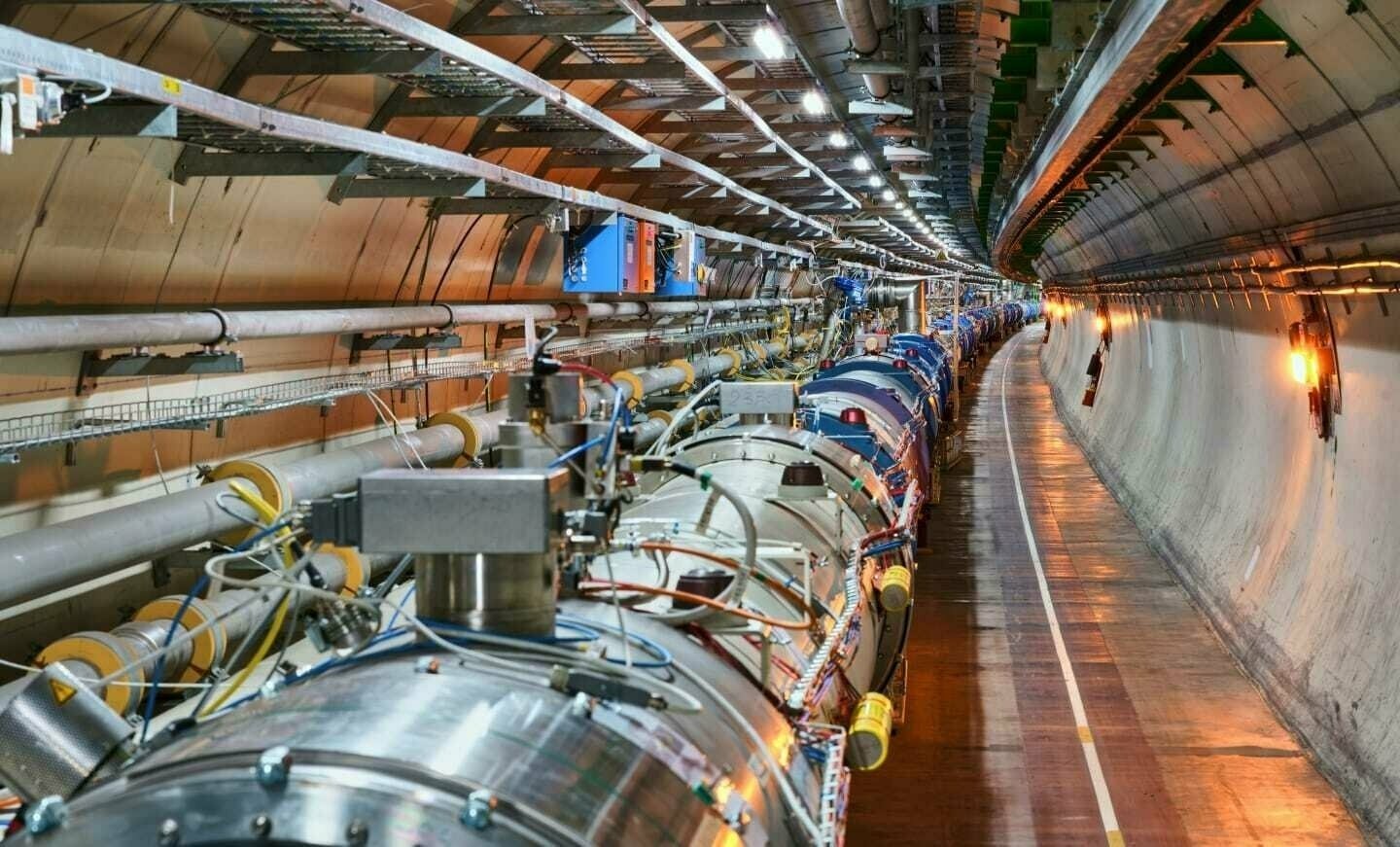

What happens when particles collide at the speed of light? Something similar to the Big Bang. This is the subject of elementary particle physics studies conducted by CERN, one of the world’s largest scientific laboratories. The institution, which is in Switzerland, is best known for its Large Hadron Collider, a giant ring 27 km (17 miles) in circumference, made up of thousands of superconducting magnets and equipped with accelerator structures to increase the energy of the particles, which are made to collide at four points around the machine. Four particle detectors, including ATLAS, pass through the tube. That’s where Bardo performs her role as head safety engineer.

8.30AM Bardo arrives early to start work. At first glance, it looks like we’re in a barren industrial park. But the main attraction is somewhere else: buried deep underground. The eerie setting is brightened up by a giant fresco painted onto one of CERN’s many buildings. Built in 1954, this scientific superstructure covers 526 acres (213 hectares) and is as atomized as the particle physics it was created to study. About 17,500 people from all over the world work here, 10,000 at any one time. For Bardo, being part of a multicultural workforce is a major perk. “I started my career at the ESA [European Space Agency]. I wouldn’t be able to work in a strictly French-speaking environment. I love being surrounded by people from different countries. It makes my job all the more challenging because different cultures assess risk differently,” says Bardo as we enter an ordinary-looking building.

I’m dying for a full tour of the facilities, but I have to be patient before venturing into the depths of the “cave,” as the ATLAS lair is known internally. Bardo leads us first into the control room, one of her three workspaces. She plays a fundamental role as no physicist or mechanic is allowed to go underground without supervision. “Right now, the room is a bit empty because ATLAS is in its second long shutdown. This data collection and maintenance phase is essential before activities resume, which is scheduled for spring 2022. Then, when we are in the ‘run’ phase, no one will be allowed to go down, except in specific cases, such as to carry out brief maintenance operations,” says Bardo.

In the control room, the atmosphere is calm, with a few people whispering. But the number of screens in the room reminds us that there are busier times when the detector is in full swing. Bardo is in charge of the seven people who work at the control room desk. “Fitting in with this team was tough initially because the guy in charge was older than me and, like many of my colleagues, from Eastern Europe. But I think they understood that I wasn’t there to get in their way but rather to improve their daily lives. I think you can get people to see things in a new way if you show integrity,” says Bardo. As lead safety engineer, she tries to be firm but not authoritarian.

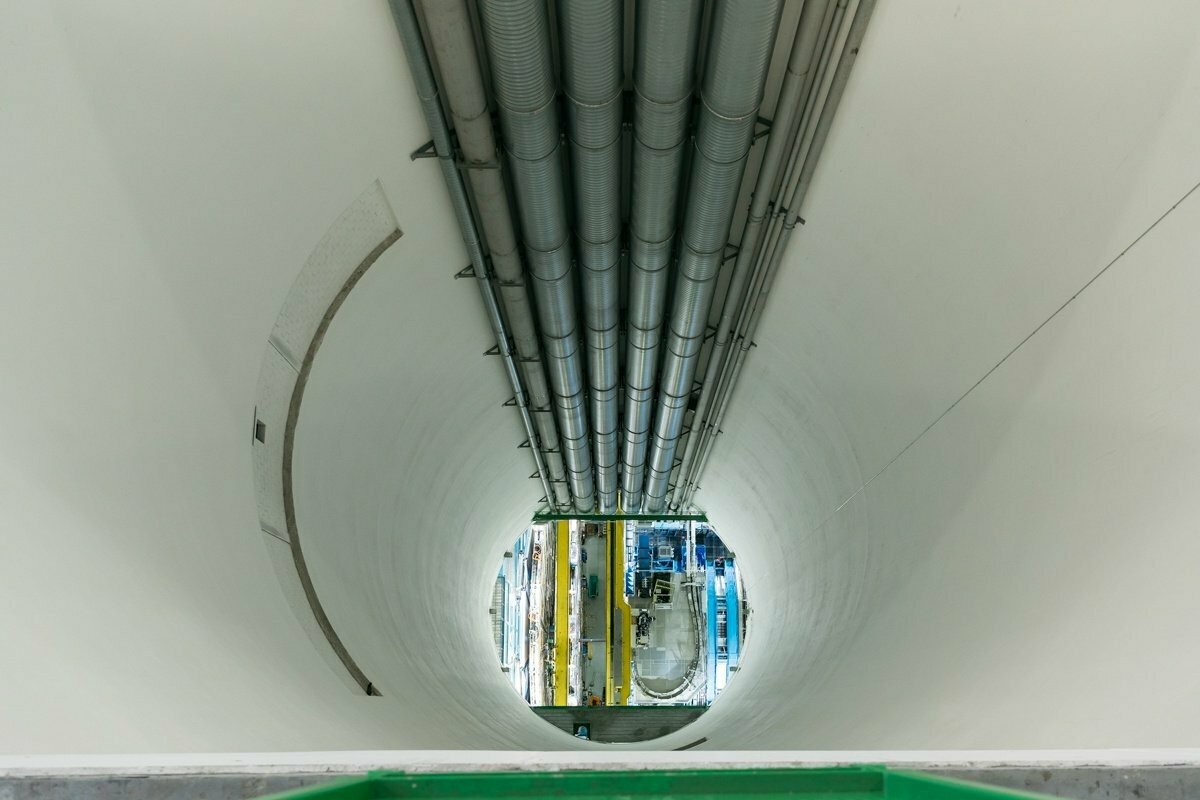

Next, Bardo takes us to see her favorite part of the building. She shows us an immense space and a deep shaft used to transport equipment straight to the core of ATLAS. My heart skips a beat as I lean over the green platform that sits above this void. “The maneuvers are incredibly risky, as there’s no room for error when you’re lowering equipment 100 meters underground,” says Bardo.

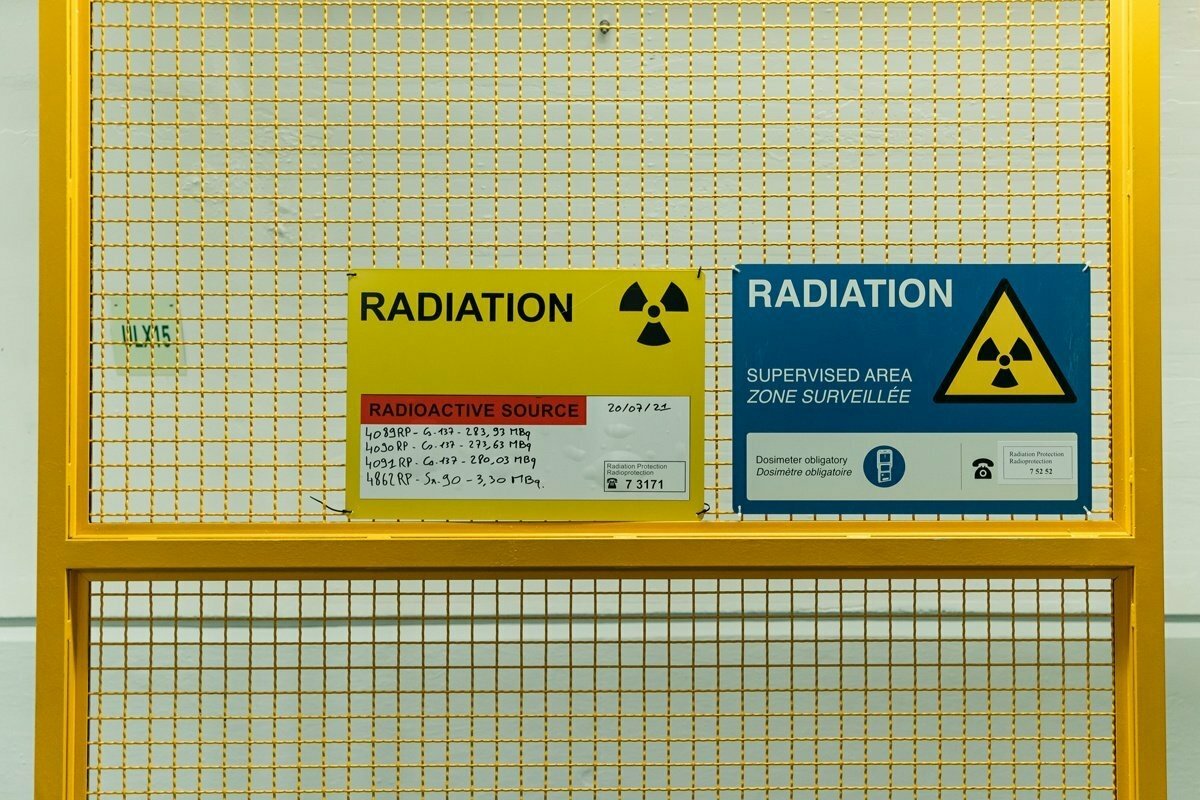

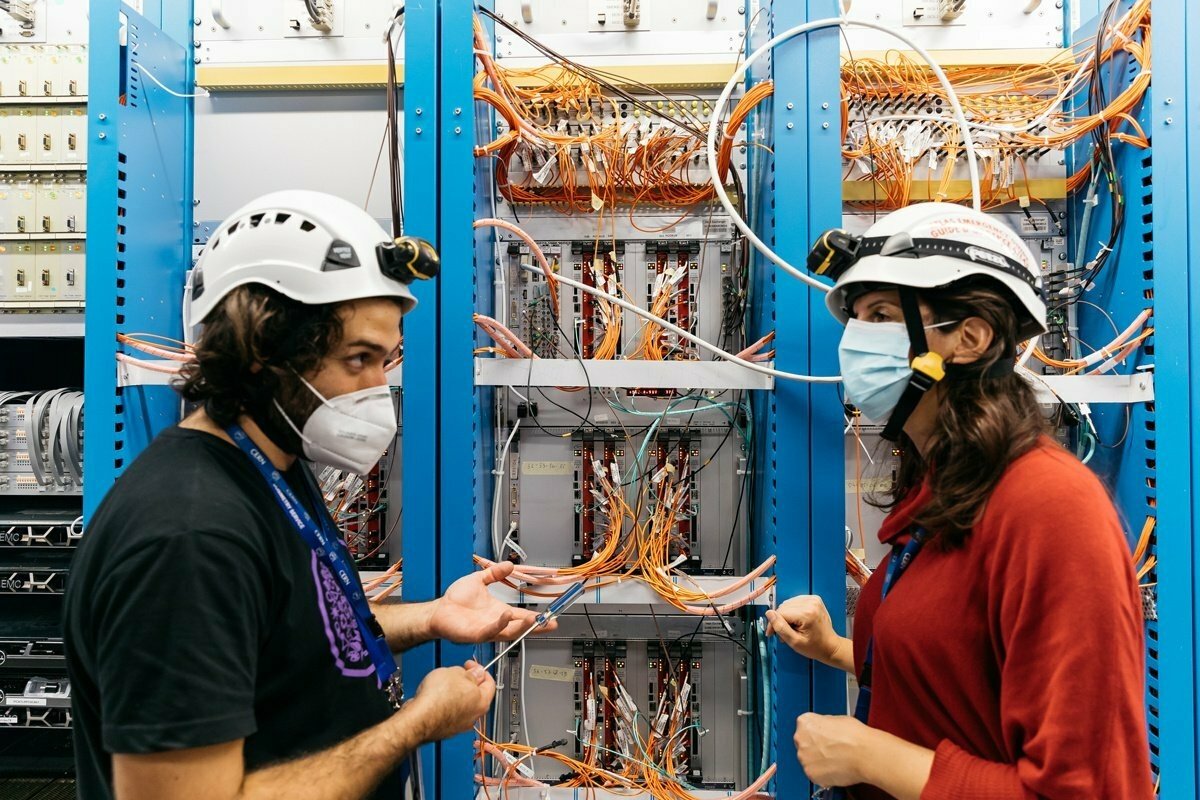

When we come to a sign for radiation, I feel like I’m in an episode of Dark, the German series shown on Netflix where kids disappear in mysterious circumstances from a village. It’s a valid question: what are the radioactivity levels here? The dosimeter hanging around Bardo’s neck isn’t exactly reassuring. “It’s just a safety measure,” she says. “The real danger comes from working high up, especially as some people like to think they’re acrobats! I’ve had people run in to tell me that someone has been electrocuted or has fallen off scaffolding. Fortunately, neither of the accidents was serious. In any case, it’s my duty to provide everyone with the right training, the right equipment and to issue warnings and reminders when necessary. There are lots of challenges, but that’s clearly what I like about working here. I left my previous job because there wasn’t enough risk,” Bardo says. There’s certainly plenty here. Everything is controlled down to the millimeter because things can quickly turn serious. “We’ve had two or three fires, one of which happened just before Christmas. I found myself at home with my family in the middle of the night guiding the fire trucks remotely. Luckily, it never got out of hand,” she says.

Once we’re in the elevator that will take us to the center of the Universe – or something close to it – Bardo stops for a few seconds and peers into a small camera. With visual recognition software that’s worthy of Minority Report, this opens up access to the “cave,” the lair of ATLAS. My method of entry is less exciting as a simple visitor’s badge is enough to grant me access. Our long ride down takes several minutes. “If someone attempts to force unauthorized access, they’d better be able to justify it,” she says.

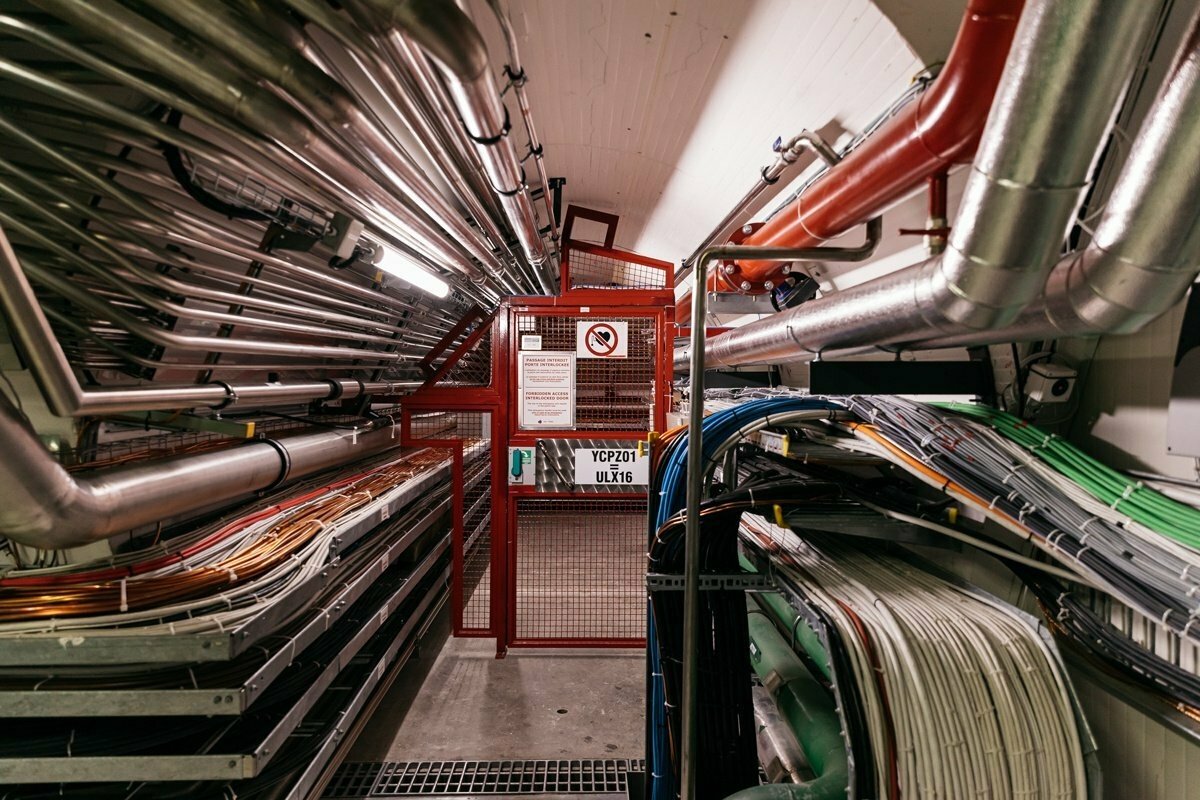

We’re now face-to-face with the hidden beast, some 330 feet (100 meters) underground. Countless cables and tubes feed into a mass of panels that Bardo still finds awe-inspiring. It’s like a strange sleeping creature that lets us get close, tiny earthlings playing sorcerer’s apprentice, electrified by the prospect of cracking the greatest of mysteries. “You’re lucky you get to see it because when activities start back up in a few months, it will no longer be possible,” she says. The ATLAS detector is huge: 46m (150ft) long, 25m (82ft) high and 25m (82ft) wide. It weighs 7,000 metric tons (7,716 US tons), which is about the same as the Eiffel Tower, making it the largest particle detector ever built. Along with the CMS detector, which is also at CERN, it’s known worldwide for having recreated the interactions at play in the Higgs Boson. This makes it a veritable superstar with elementary particle enthusiasts everywhere.

What’s more, it must be constantly revised and expanded to improve its performance and collect more data. During technical operations, Bardo has to ensure everyone is safe, including the technician I can now see changing one of the detector panels.

Bardo and I now climb what seems like a never ending series of stairs. “You can see how the risk is also cardiological! I’ll never need to work out at home again,” she says. When we walk along the suspended walkways, I start to feel a little dizzy again. “At first, I wasn’t comfortable on these platforms either,” she says, reassuringly. On average, Bardo spends three to four hours underground each day but says she doesn’t feel overwhelmed by the lack of natural light. “I love spending time underground with the teams,” she says.

I look right and left, but there’s nobody around: I can see only thousands of wires. Within ATLAS, cables, tubes, and connectors of all types intertwine until they merge into their own special aesthetic. Although it resembles a no man’s land, we’re not alone in the cave. “The structure is so big that you don’t realize there are sometimes around 50 of us working underground in the cave,” says Bardo.

During her inspections, Bardo chats with a technician from Italy. Even though she works in a male-dominated environment – about 20% of staff at CERN are female – she sees it as a positive instead of a negative. “When you’re a woman, people remember you more, and I think they appreciate our being here. I’d say my weakness is that I probably mother them a little too much! And I’ve never experienced any inappropriate remarks. CERN is trying to recruit more women, and I’d recommend coming here to work,” says Bardo.

5.00PM To get back to ground level, we retrace our steps. We meet up with two of Bardo’s female colleagues in her office. She’s their supervisor and, on a clear day, they all have a view of Mont Blanc. After a day of fieldwork, it’s time to check her emails. “Even though I have office work to do, I’ve learned my job primarily in the field,” she says. A few hours of work still lie ahead. “At CERN, we don’t clock in and clock out,” she says, smiling. She hopes to continue to contribute to this incredible odyssey. “My contract ends in 2024, but I’d really like to stay for the next long technical shutdown,” says Bardo. “There will be huge challenges as we upgrade the detector to increase the quality and amount of data we get. That would take me up to 2030!”

Translated by Andrea Schwam

Photos by Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook on LinkedIn and on Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

Inspirez-vous davantage sur : Les tendances du monde du travail

Why are workers quitting after getting promoted?

29% of promoted employees quit within six months of their promotion—but why?

13 mars 2024

Overemployment: Reinventing moonlighting in the digital age

Read personal stories from those juggling multiple roles, and expert insights on the trend from a future of work strategist.

29 janv. 2024

7 things that will happen at work this year

What's in store for the world of work this year? These 7 expert predictions...

24 janv. 2024

You were doing what? Here’s what a ridiculously detailed time study says about the US

Gaming? Sleeping? Working? This year’s American Time Use Survey shows what Americans are up to — minute by minute

14 août 2023

From affirmative action to teenage work injuries: Your July working-world recap

Check out our monthly recap and stay updated on the latest news and buzz in the world of work

01 août 2023

La newsletter qui fait le taf

Envie de ne louper aucun de nos articles ? Une fois par semaine, des histoires, des jobs et des conseils dans votre boite mail.

Vous êtes à la recherche d’une nouvelle opportunité ?

Plus de 200 000 candidats ont trouvé un emploi sur Welcome to the Jungle.

Explorer les jobs