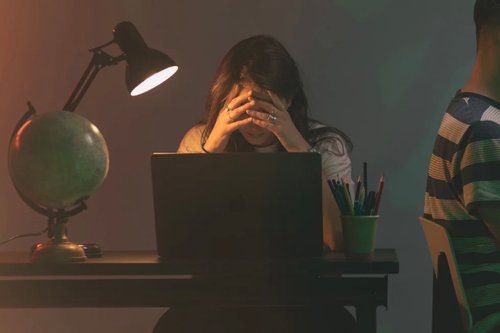

The emotional burden of care work

27 may 2020

6 min

Journalist & documentary filmmaker

Overworked, underpaid, and undervalued: this is the plight of social care workers, thrown into the limelight by the Covid-19 crisis due to their vital work in fighting the pandemic.

There are an estimated 1.6 million social care and support workers in the UK who work directly with vulnerable individuals or groups in society such as the handicapped, the elderly, and those living in poverty, or struggling with addiction. Providing physical, mental, and social support in this way is challenging, intense work that can take its toll emotionally, even in less turbulent times. But the Covid-19 crisis has shed some light on the precarious situation of care workers.

Statistics show that social care workers are twice as likely to die with coronavirus as the general population. A lack of access to tests, PPE shortages, and care home clusters are also impacting stress levels. It’s no wonder experts are warning of mental burnout, exhaustion, and even PTSD in the sector.

Here we speak to social care workers about the extraordinary and unprecedented emotional challenges they are facing—and how they manage to care for themselves as well as others.

What makes social care work emotionally demanding?

Working with vulnerable people can be an intense experience. It can give rise to emotional challenges and negative emotions, including the following:

Establishing boundaries

When you’re working with people who have complex and acute needs it’s often difficult to set boundaries. Niall O’Conghaile, 41, works as a support worker in a housing project for recovering addicts in Manchester. He said that finding the right balance is highly demanding but necessary. “You become friends, but you’re employed to look after them,” he said. “You might leave the job so they can’t come to depend on you too much. It can be exhausting.”

Feelings of guilt

Many social care workers feel guilty switching off at the end of the week when their clients are unable to do the same. Daniella Russo, 30, used to work for a domestic violence support agency. She said, “The most emotionally demanding aspect was feeling like I’d not done enough for someone. It’s important to realize your emotional capacity while trying to support people at the highest risk of harm so they can be safe.”

A lack of training

Care workers also worry that they don’t have adequate training to feel safe and do their jobs properly. O’Conghaile once had to use physical intervention to deal with a client’s violent outburst, despite having received no training in this area. “This client was severely impaired and couldn’t talk or understand language. He would very occasionally lash out. Once he punched me in the face so I had to physically restrain him,” he said. The lack of support O’Conghaile received afterward was particularly disheartening and led to him leaving the job.

Exhaustion

The heavy workload and unsociable hours are additional stresses. Arthur Brown, 31, an autism support worker in Bristol, finds the unpredictable hours, particularly testing. “You need to be there 24 hours a day. Sunday could be a 6:30 AM start, or it might be a night shift. When I worked full-time—150 to 200 hours a month—it used to have quite a big impact on me. I was totally exhausted,” he said.

Why is there a high burnout rate?

A recent mental health study revealed that one in three social care workers experience burnout at some point in their careers. Brown explains why. “The most draining part is seeing people in distress. You only realize this once the adrenaline has gone. I have definitely felt overwhelmed, but when it happens I go into fight mode to sort things out.”

Housing project support worker O’Conghaile agrees that the nature of the job is intense. “It’s a fast-moving world. If something happens you have to go back to work and continue with the rest of your day. These people still need support, so you can’t get too carried away with your own emotional needs. You need to put theirs first,” he said.

When you have to deal with violence, grief, addiction, or ill health in a professional setting, it can cause an emotional shut-down, known as depersonalization, compassion fatigue, or vicarious trauma. Russo described how a former colleague at the domestic violence support agency dealt with the stress of her job. “She had to take Night Nurse when she got home, just to switch off and be able to sleep,” she said. Russo herself experienced burnout. Her anxiety became so severe that she had to take a break from her job.

Work stress also contributes to high staff turnover. A recent report showed that almost one in three people leave their jobs every year and staff shortages are common. The aftermath of Covid-19 will no doubt cause these figures to rise further. Russo says that this situation is dangerous, both for employees and service users. “Due to high caseloads and lack of funds because of Government cuts, very little time or resources is given by organizations to monitor their workers’ wellbeing. So it falls on the worker. The pressure to self-care and support your peers become additional emotional work, on top of your own work.”

When social care workers struggle with mental health problems themselves, this cocktail can become toxic. Michael Mendones, 45, is a retired occupational therapist from London. He is bipolar and used to be a patient in the center he recently worked in. “One in five people with my disorder commit suicide,” he said. “I thought it would be a great story, that I used to be an in-patient where I am now a staff member. I was foolish, it was too stressful. I took early retirement due to ill health and stress. But I learned it’s not selfish to replenish yourself. If you burn out, you can’t help others.”

How do social care workers strike a work/life balance?

There are ways to manage stressful jobs. Here, social care and support workers share their well-being tips:

Leave work at work

Russo learned how to keep work and her personal life separate the hard way. She says you need to establish boundaries—and stick to them. “Turn your work phone off, leave on time, and debrief beforehand if you need to. Unfortunately, if you are in the care sector, work follows you! Surround yourself with supportive friends, and learn to say ‘no’ to friends and family who expect emotional labor from you. Don’t underestimate how tiring, draining, and triggering this can be,” she said.

Do regular exercise, yoga, and meditation

Relaxation methods such as yoga are common stress-relief tools among those in the sector. O’Conghaile from Manchester does tai chi and qigong as a way of dealing with work stress. He also walks to work every day and has continued to do so during the pandemic. Whether it’s exercise, cooking, or meditation, what’s important is finding something that relaxes you.

Seek professional help and supervision

Team support makes a huge difference. Autism worker Brown has always experienced a supportive atmosphere at work. “There are a lot of resources in the sector if you yourself are struggling,” he said. “There’s still a bit of a stigma around mental health, it feels like you can’t call in if you’re having a breakdown. But things are changing. I feel more emotionally supported than in any other job.”

Adrian Deen, 30, is a medical student. He previously worked as head of support services at an HIV charity in London, where he felt incredibly supported due to monthly therapeutic supervision offered by his employer. As part of a small team, he felt comfortable confiding in colleagues when things were difficult. “I know this isn’t the case in the NHS and I’m already mentally preparing for this,” he said.

Focus on the positives

The average wage of social care workers is shockingly low—it stood at £8.10 an hour in 2019, below the basic rate paid to supermarket employees—which clearly indicates that they don’t put up with the tough working conditions for a fat pay packet. Those who pursue this line of work do so for more altruistic reasons. They feel their contribution to society is meaningful and makes a difference in their community. In fact, one study revealed that 29% of health and care professionals in the UK believe it tops the list of fulfilling professions, outstripping the arts, entertainment, and law.

For Brown, working with people who have autism has dramatically changed his outlook on life. “You really start to see humans in a different way,” he said. “I’ve seen people come into the job and be blown away. They start to think very differently about the world, usually in a positive way. We’ve got a lot to learn about language and our brains through them [those with autism].”

O’Conghaile agrees about the high levels of job satisfaction. He left his customer service job to work at a day center for people with learning difficulties. “I much prefer working with people with learning difficulties than the public. They’re much nicer. Most of them appreciate the help that you’re giving them,” he said.

Social care workers are often deeply passionate about their line of work. They simply want better conditions—in terms of pay, hours, and support—to do their jobs to the best of their ability. The Covid-19 pandemic has meant that finally, the Government has to listen to union leaders, employers, and social care workers themselves. Here’s hoping that one positive to emerge from this health crisis is that these professions will finally receive the recognition they deserve.

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

Más inspiración: Salud mental en el trabajo

Harnessing emotional intelligence at work: Turning feelings into strengths

Emotional at work? Instead of shutting down your feelings, try making them work for you.

15 abr 2024

What is psychological safety and why does it matter?

Discover how psychological safety boosts innovation and teamwork, and learn to cultivate a culture where every voice is valued.

13 mar 2024

Stress at work is contagious … Try not to catch it

Unfortunately, a face mask won’t protect you from stress, but here’s what will.

15 feb 2024

How to get things done in a crisis

We aren’t just living in times of crisis – we’re living in times of back-to-back crises. Yet, we also live in a productivity-focused world...

04 ene 2024

How to make the most of a bad performance review

Performance reviews can be stressful at the best of times, but what happens when you receive negative feedback?

06 dic 2023

¿Estás buscando tu próxima oportunidad laboral?

Más de 200.000 candidatos han encontrado trabajo en Welcome to the Jungle

Explorar ofertas